By Budd Davisson

Exclusively for Airbum.com

photos as credited at end

At this point in America's life span, it has become difficult

for the politically correct amongst us to admit that the

firearm is as much a part of America's history as Old Glory,

the hammer and the horse. The firearm was an integral part

of many chapters of our development, most of them heroic,

some shameful, but it was there none the less. For the frontiersmen

and those carving a nation out of a wilderness, the firearm

was at least as critical to their survival as the axe and

plowshare.

The development of the firearm in colonial America is actually the story of the development of America itself. Further, in the first century and a half, beginning in approximately 1700, it encompassed the rise of a thoroughly American art form, the Pennsylvania/Kentucky long rifle (although many were also made in Virginia and the Carolinas). In the long rifle, we have an artifact that was forged by the needs of its environment. Then, as time went on, the culture of the people subtle changed it until it became as uniquely American as the jazz and hot rods of a much later era.

The long rifle was a by-product of the settling of the southeast corner of Pennsylvania. When William Penn began sending settlers up the rivers, which came together at Philadelphia like fingers in a glove, he unwittingly set in motion a long-term cultural event. Each of the parties that traveled up into the wilderness used the rivers as their super highways to travel northward because the topography of the land worked against travel east and west. Long lines of parallel ridges made travel via rivers the natural decision. The rivers deposited these groups of settlers in a fan shaped pattern that started in the west near present day Lancaster on the Susquehanna and continued eastward in an arc until they reached the Easton/Nazareth area on the Delaware. This was to become the heart of the American arms industry until the industrial revolution of the early to mid- 1800's developed mass production in the Connecticut River valley and the government established armories at various locations throughout the young nation.

Thinking of Pennsylvania today, it's hard to imagine it at the beginning. Traveling up river for those first travelers must have seemed as if they were being sent to colonize the moon, it was so far removed from the civilization they had known in Europe. Many of the groups were German in origin, but all knew they were going to have to be totally self-sufficient. They couldn't run across town for a bolt or an axe head. They couldn't assume they would have any help in an emergency so, to guarantee their survival, their group had to be completely self-contained. Every skill thought to be needed in their new environment had to be part of the group. This included gunsmiths.

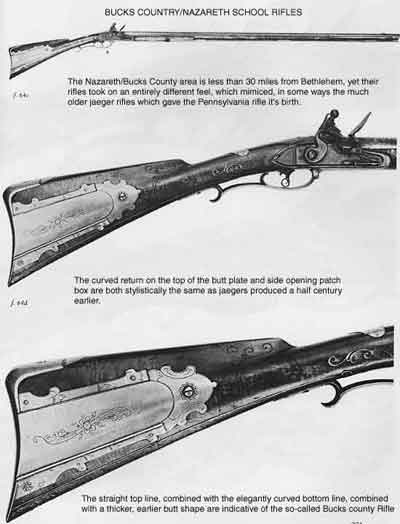

Those early gunsmiths, circa 1700-1725 brought with them the skills and thought patterns, which had been part of their training and practice in Europe. Their rifles, called jaegers (hunter), were stocky, short barreled weapons (30") usually of .60 caliber or larger and often were smooth bore. The butt stocks were thick and their general outline was purposeful but hardly graceful. They did, however, incorporate the German fetish for function and their flint ignition locks worked reliably.

As Jaegers wore out and were gradually replaced by locally produced

rifles, the Pennsylvania environment began to have several effects.

For one thing, knowing that they couldn't easily replace the

powder and ball expended each time they pulled the trigger, accuracy

became critical. Each time they pulled the trigger, they wanted

to be bringing home a buck or a squirrel. Where the jaegers in

Europe were primarily target shooting or hunting for sport, in

the new land, shooting was a matter of survival.

Got to Page Two