Page Two

Accuracy with any weapon is driven by

many factors, but prime amongst those is the distance between

the front and the rear sights. The longer the distance, the more

finely the marksman can control where the lead ball will go.

This begs for a longer barrel. The longer barrel gives yet another

side benefit in that the ball spends more time captured in the

barrel with the expanding gases pushing it faster and faster.

There is a point of diminishing returns with this concept, obviously,

as friction and expansion space become part of the equation.

However, there was no way those early gunsmiths could measure

the velocity of their bullets, so, as far as they were concerned,

longer was better, when it came to velocity and accuracy. By

the 1750's the length was continually being increased until the

standard barrel was 42"-44"

in length with four feet not being uncommon.

The original Jaeger barrels were good sizes chunks of iron, usually measuring at least1 1/8" across at the breech end. Make a barrel like that three and a half feet long and you have 12 to 14 pounds to lug around the woods. Not a lot of fun and not very practical. At some point beginning around 1760 someone figured out that a high speed, slightly smaller ball, killed just as easily as the huge, lumbering lumps of lead being thrown by the jaegers. In addition, the number of balls that could be cast from a pound of lead jumped astronomically. A pound of lead will yield only 17 .64 caliber balls while over 37 .50 caliber balls can be cast and 51 each of .45 caliber. Also, the woodsman was just as likely to be killing squirrels as bucks, so a smaller caliber wouldn't mangle the smaller game as much. If they were going after bigger game with the smaller ball, they just poured more powder down the barrel to push the ball faster. This gave rise to a general trend that for the next 50-75 years would see the caliber decrease gradually to the point that .40-.50 caliber would be common by the turn of the century. This also meant the barrels could be slimmer and, therefore, lighter. As the long rifle spread into other regions of the country, including the south, and small game became the primary target, calibers worked down even further until .32 was common and .28 wasn't unknown. These were true "squirrel rifles."

Many jaegers had a curiously shaped octagonal barrel that carried over into the earlier forms of American long rifles. This barrel, termed "swamped," tapered from the breech towards the muzzle then, at approximately ten inches to a foot from the muzzle end, it would flair out again. The practical reason for this has never been fully explained, although it does shift the center of gravity of the barrel back closer to the shooter's hands giving the firearm much better balance. If, however, that's the reason, why flair it back out towards the muzzle? In all probability, it is a stylistic trend. At any rate, this type of barrel began to disappear by the 1790's and, by the turn of the century, was seldom seen, having been replaced by the much easier to manufacture straight octagonal barrel.

Incidentally, in case you're wondering, barrels locally manufactured used using two basic methods. One involved taking several five or six foot long ribbons, or "skelps", of iron roughly half inch thick and an inch wide and hammer welding them together at one end while red hot. Then these strips were heated and wrapped around a mandrel before being hammer welded together and forged to a rough octagonal shape. The mandrel was withdrawn (that must have been a fun job!), the hole was bored smooth and straightened, then rifled in a home made rifling bench, one groove at a time.

A second method involved folding a thick, single piece of metal around the mandrel lengthwise. This was hammer welded smooth along the bottom in a scarf joint. This produced barrels that sometimes split along the seam with heavy loads.

The octagonal shape, which was initially hammered into the rough blank, was draw-filed to final shape by hand, although water driven grinders were undoubtedly used in larger production shops.

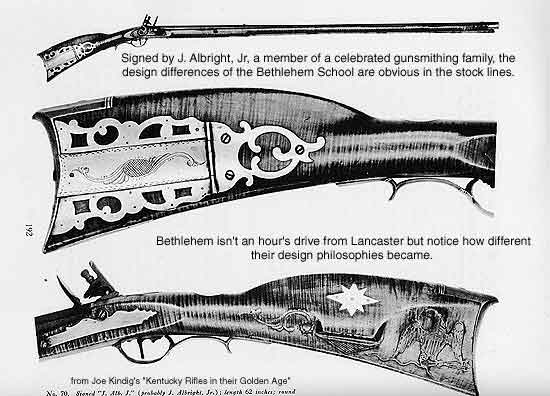

As the rifles developed, a curious trend started in which each location or township developed distinctive styles not only in decoration but in general shape. Some of these locations are no more than 15 miles apart, but the difficulty in traveling that distance, meant the artisans worked in relative isolation so their ideas were less influenced by those far away. Each of these styles, which are termed "schools", were named after their location (Lebanon, Reading, Dauphin, etc). While generalities can be made concerning the differences in the styles it's dangerous to take these as concrete rules. In the first place, gunsmiths often migrated from one part of the territory to another, taking their ideas with them. Also, as time went on, the styles changed and, in some areas, the styles changed faster than in others. A classic example of that is the general shape of the butt stocks.

Through out the region, as time passed, the butt stock became thinner and thinner. Where the jaeger had a flat, 2"-2 1/4" or thicker butt plate (picture a full dimensioned 2 x 6) that had little curve to it, the butts gradually worked their way down to 1 1/2" and less thick. Also, the flat shape of the butt plate gave way to an increasingly curved surface. By the time flintlock ignition began to give way to the percussion cap, roughly 1840, the rifles were extremely thin and the curve of the butt plate was sometimes quite exaggerated.

The side-view shape of the butt was another of the distinctive

differences from area to area. Nazareth and Bucks county, on

the east, retained straight lines, similar to the jaeger, where,

on the other extreme, barely 25 miles away, in Bethlehem, rifles

often had extremely curved shapes, sometimes termed "Roman

nose" stocks. Travel less than an hour further and the stocks

become very linear as is typical of rifles from the Lancaster

area.

Go to Page Three