PAGE TWO

|

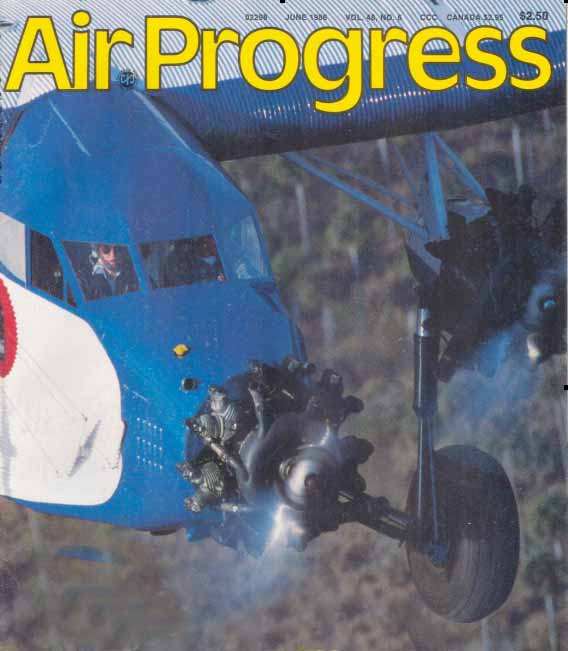

No that's not a dissatisfied

customer leaving the airplane. All the time we were working with

the airplane, they were flying a non-stop string of jumpers. |

"I had been flying Lears and MU-2s all over the

country hauling 'freight and checks and I was about burned out. I was

tired of flying all night, every night, so, when Al asked me if I'd

like to barnstorm the Ford, I couldn't get packed fast enough."

We caught up with Ed Rusch and his barnstorming Ford almost by accident.

Cruising up and down the airshow line at the 1986 Valiant Air Command

Warbird show in Titusville, Florida, we came across the Ford—looking

terribly out of place—at one end of the ramp. I stumbled out

of the car and found myself in an instant conversation with Ed. Although

we were total strangers, my interest in his airplane was all that was

needed to get things started on a friendly note. Although Ed looks

like the type that is slow to anger, I got the feeling that all it

would take is a few disparaging remarks about the Ford to bring him

to an instant boil. Even then, however, the only outward indication

would be the subtle sound of his clenched teeth snipping the end off

his cigar.

|

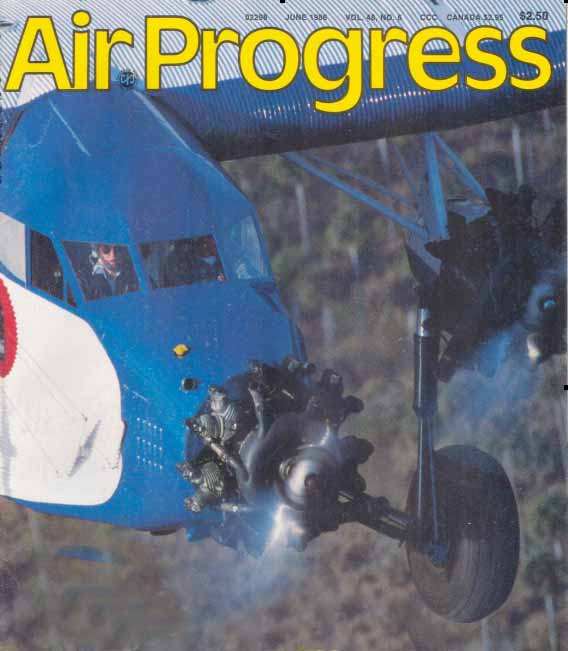

It comes off the ground in

an absolutely level attitude. |

Rusch and the Ford were only visiting the show for the day, since

they had taken up semi-permanent residence at Dunn Air Park on the

north side of Titusville. After several months of hopping

about the country, they had decided to try working the local tourist

trade and they may still be camped there today.

Early the next morning I found myself strapping into the right seat,

while Ed played stewardess, ticket taker and captain in the main (and

only) cabin. Letting my eyes roam around inside the airplane I had

to grin just a little: As an example of aeronautical design the 4-AT-B

is certainly a fine bridge. Everywhere you looked healthy bits of aluminum

angle were riveted to another healthy chunk of aluminum. The massive

main spar ran through the cabin, decreasing headroom by nearly two

feet but providing the forerunner of overhead baggage bins, as that

was where you stowed your bags. Leaning forward and looking down the

leading edge, the rolled ribs in the skin, which formed an exoskeleton

betrayed themselves as an uneven collection of sixty-year-old dents

and patches.

The panel was archaic, as you'd expect, but impressively simple, which

you might not expect. However, when you consider that the three J-6

Wrights (230 hp each) have fixed pitch props, that eliminates the need

for manifold pressure gauges and prop controls.

Remember the solenoid buttons that stuck out of the floor of old Ford

trucks? You turned the key and mashed the button with your foot and

the flathead V-8 sprang into life. Ditto the 4-AT-B. Three typically

Ford starter solenoids poked up between the two sets of rudder pedals.

Mash one, count two or three blades, and that particular engine was

running. Like we said, no muss, no fuss.

AS A SINGLE PILOT OPERATION (VFR, OLD REGS, remember?), doing the run

up was about the most complicated part of the flight and this was only

because of the brakes. The brake is a hip-high lever poking up between

the two seats. A true "Johnson Bar," you pull back for both

brakes, left for left, etc. Which is fine, but it has no lock. So,

in doing the run up, when solo, you have to cross one leg over in front

of the bar and push backward with your thigh to keep the airplane in

one spot. Ed motioned for me to follow him through while he made the

first takeoff. I glanced back ('way back) at the ailerons to make sure

they were centered and mentally made a note as to the position of the

control wheel spokes, when centered.

The tailwheel is a full swivel job so throttles, rudder and Johnson

Bar got us out to the center of the relatively narrow (for a Ford)

runway and Ed moved the throttles to the stops in one smooth motion.

Then, without waiting even a second, he straightened out his arm, two

arms actually, and pushed the wheel full forward. We were barely moving

fast enough for the airspeed to be two digits and the tail staggered

into the air giving an absolutely unobstructed view of the runway.

With only 690 horses on a 10,000-pound load, you wouldn't expect it

to leap off the ground. And it didn't. But, the Ford still surprised

me when the plane floated, literally floated off the ground in a nearly

level attitude. I glanced at the ASI and it read 60 mph! Not bad, considering

we were hauling something like eight people back in the tourist class

section. Later in the day, we followed Ed with our Seneca. He was carrying

about a dozen skydivers up to 4000 feet and it was all we could do

to keep up with him in climb. So much for progress!

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|