It was cold. SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Otto Skorzeny turned his back to the biting wind, burying his hands in the deep pockets of his SS topcoat. As he chatted with the bald-headed man he'd come to rescue, he glanced at the small band of exhausted Wehrmacht soldiers huddled in the shelter of their broken glider. They'd just finished clearing a tiny patch of level ground, prying and pulling and rolling away the larger boulders as best they could. Their only hope of rescue lay in that rock-strewn, furrowed patch of ground a couple of hundred feet long perched on the side of the mountain.

Skorzeny was nervous. Der Fuhrer had charged him with finding and rescuing IL Duce. Skorzeny had found Mussolini held captive in a hotel on the peak of the Gran Sasso Massif in the Abruzzi Molise. A nearly perfect prison location, it was at an altitude of 9,050 feet and accessible only by cable car. Skorzeny looked across the flat area to the cliff and the thousands of feet of empty space beyond and stamped his feet, trying to keep warm. It was September, but the sun didn't help at that altitude. Then he heard the faint drone of an engine laboring helplessly in the thin air.

He shielded his eyes and strained to see the little airplane. He had originally planned to use a Focke-Achgelis Fa-223 helicopter for the rescue pickup, but it had broken down at the last minute and he had to rely on a conventional airplane. As it came closer, he looked again at the tiny landing area and grimaced. At this altitude, impossible! The airplane was almost there, its legs dangling like a praying Mantis and its wings festooned with all manner of flaps and slats. Then to his amazement, the spindly airplane touched down and lurched to a halt with yards to spare. A Fieseler Storch had arrived to pluck Benito Mussolini from one of the most impenetrable spots on earth.

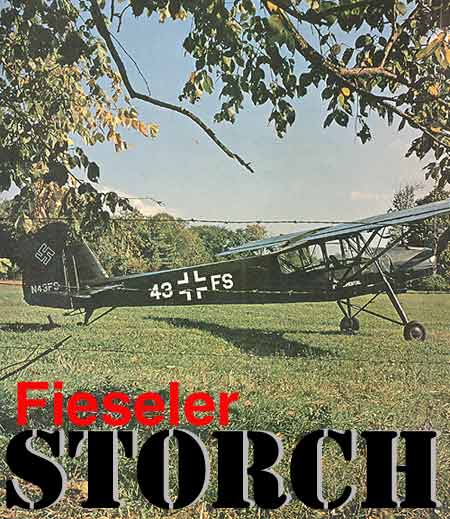

More than just another ugly face, the Storch is more kangaroo than stork. (Photo: Glenn Giere)

|

That was the Storch's only moment of glory. Most of its life was back breaking, thankless labor as a tool, a method of transportation. It earned no accolades or medals. It was a mud covered, beat-up jeep of an airplane, with only one redeeming feature—it could get in and out of places most airplanes wouldn't use as crash sites. An emaciated buzzard, it followed the German army wherever it went and acted as eyes when they had none; as an airline where none could exist.

Officially, the Fi-156 Fieseler Storch began in 1935 as Gerhard Fieseler's answer to an air ministry specification for a general purpose airplane that could take off and land in an extremely short distance. Fieseler's chief designer, Reinhold Mewes, decided for ease of maintenance that the airplane should be completely conventional in its construction, and so utilized a steel tubing and fabric fuselage with wooden wings. The engine was the then-common Argus As 10C inverted V-8 aircooled 240-hp model. Aerodynamically Mewes decided to go to the other extreme and use the most advanced techniques available to produce the ultimate in slow speed performance. Accordingly, the big 46-foot wing a had full-length fixed slats (projected movable slats never materialized), Fowler-type flaps that increased wing area by 18 percent, and ailerons that drooped with the flaps when they were extended past 20 degrees.

To keep up with the tremendous demand for the Storch, production was boosted by retooling the Morane-Saulnier plant in occupied France for the Storch. The Morane-built airplanes were modified and the wings were redesigned to use aluminum. After the war, the airplane was so popular for towing gliders that Morane produced a post-war model with a radial engine and strengthened fuselage.

Until recently, the only Storch in America was hiding in the Smithsonian's storage facility in Silverhill, Maryland. But last year, Gert Frank of Kensington, New Hampshire, single-handedly more than tripled the U.S. Storch population. Frank is a captain for Northeast Airlines and an ex-fighter pilot, but most of his free time is spent burrowing into forgotten corners of the world, buying and importing strange foreign flying machines. The mainstay of his exotic airplane importing business is the DH Tiger Moth. But in response to the growing interest in unusual machinery, he has started importing all manner of wonderful things. He has brought in several of the DeHavilland twin-engine biplanes, the Rapide and Dragon; a whole bevy of the complex and beautiful BMW Sahara motorcycles and sidecars; a Kubelwagen, the Nazi version of the Volkswagen Thing (or is it vice-versa?), and Fieseler Storches.

My own involvement with the Storch started one evening when I was sitting around with a friend browsing through Trade-A-Plane. Suddenly my friend let out a whoop, "Fantastic! There's a Fieseler Storch for sale!" I dashed for the telephone. Thus, I came to know Geert Frank and the Great Storch Expedition was underway.

In 1972 Geert Frank was way ahead of his time and was importing all manner of unique, wonderful flying machines.

|

Frank was in the process of painting the Storch so it would be a while before we'd be able to see it. In the meantime we kept our local airport in a tizzy by regaling them with stories of the Storch and the fantastic things you could do with such an airplane. When this thing started, nobody had ever heard of a Fieseler-Storch, but before long we produced picture after picture and all the local tire-kickers immediately fell in love with its obvious lack of charm. We even formed a sub-rosa chapter of the International Aerobatic Club, but ours was the FSAMS, the Fieseler-Storch Aerobatic and Marching Society. The airplane generated more local excitement than anything since the Thruxton Jackaroo. Yep, doesn’t take much to get us all pumped up.

One evening, the long-awaited call came: The Storch was ready to be flown! The only day we were guaranteed good weather was in the middle of the week, so hurried plans were made, airplanes fuelled, cameras loaded and we all headed north to New Hampshire, in search of the Storch.

A few hours later we were winding through the New Hampshire landscape in Geert Frank's Mercedes. Frank has a small farm, but as luck would have it, there is no place flat enough to accommodate even a Storch. He refurbishes the airplanes in his shop and then tows them several miles to a short strip he shares with a farmer. Towing is easy since the Storch's wings fold. No sooner had he explained his operation then we rounded a bend, and parked there (slouched might be a better word) was a real Fieseler Storch, complete with German colors.

Even though I had seen many pictures of the Storch, nothing could possibly convey its size and general ungainliness. It stands so high off the ground that an average man can barely see in the side windows. In fact, we doubt that there's a man alive who could step from the ground to the door sill, once the huge, multi-faceted door is pulled out and up and fastened to the bottom of the wing. This isn't an airplane, it's a three-dimensional, whimsical caricature of an airplane. Traditionally, the whole idea of aviation has centered on efficiency-getting the most speed from the least horsepower. This airplane, clearly, works on the opposite premise. If there is an airplane with more drag-producing protuberances, I've never seen it. Aerodynamically, the Storch makes a tumbleweed look slick.

I quickly scurried up the gear leg, onto the ladder, and . into the cockpit. The nose didn't even begin to block my vision because I was sitting so high above it. The cockpit area is huge, big enough to stand up in, and it's cluttered with cranks, wheels and levers, all labeled in German. The stick and rudder are where they should be, but the rudders are big cast-aluminum footprints with safety straps of their own and the stick resembles a telephone pole. The flaps are lowered by a crank, not a dainty lightplane crank, but a man-sized Model "T" Ford type crank that sticks out of the left wall. By winding in the Aus direction, wing-size boards flop out of the trailing edges and the ailerons race to catch up. In the spar carry-through structure over the pilot's head is a pointer that indicates how much flap is hanging out, and in this airplane, any flap at all is a lot.

Bicycle chain on left is run by big crank by left knee. Check out the rudder pedals.

|

Frank's Storch is an original German machine fitted with Morane metal wings. As originally equipped, it had a mount for a flexible machine gun sticking backward out of the top of the rear canopy glass. It was manned by the third passenger kneeling on the back of his folded seat. Frank didn't have the third seat installed. Bof the way the side glass is angled out, all passengers have a nearly unobstructed, straight down view of the ground

The rural runway measured just a tad over a thousand feet, most of which was a narrow path whittled through the trees. The wind was gusting crosswise, so I decided to put off the actual flying until the wind figured out which way it was going to blow. While we were waiting, Frank gave us a tour of his farm/workshop/Tiger Moth-ranch. I envy him his ambition and geographical location. How many of us have dreamed of a little place in the country, the feel of autumn closing in as we walk out to our workshop to do a little more doping or rib-stitching on our latest project!

A few hours later, we ventured forth and decided it was time to go Storching. Except for taking a long time to get the cylinder head temperature into the green, the inverted Argus V-8 started and preflighted just like any other engine, only it had a definite teutonic sound. More of a growl than anything else.

I’ll have to admit that as I rumbled through the grass to the end of the runway, I couldn’t have felt more out of place if I had tried. There was nothing about the airplane that was even vaguely reminiscent of anything else I had flown. You sit so high with so many tubes and frames cutting through your view that for a brief second, I had the feeling that I was perched well up in the branches of an old apple tree. And I was about to fall out.

You’re sitting there, your hand wrapped around an impossibly tall stick while your feet are spread wide and held to the aluminum foot prints by straps. I pointed the nose into the cut in the trees and decided it was time to find out what the Storch was all about.

Slats, drooping ailerons, huge flaps help the Storch fly REALLY slow (Photo: Glenn Giere)

|

Frank said on takeoff to keep it on the ground until I had 40 knots indicated and then to yank like crazy. He said to forget about finesse. It called for brutish control applications. Aside from the size, he said, it flew like a Cub. I disregarded the Cub analogy and locked onto the 40-knot figure. I started the throttle forward and the exhaust tone of an old circle-track stock car rumbled over me and the airplane lunged forward. I pushed forward with the stick in an effort at raising the tail, but nothing was happening. At first I thought the tail must weigh a ton. The stick pressures wer enormous. In fact, I found I could barely move it with one hand, so I wedged my shoulder against the seat and really gave the stick a shove. The tail sagged into the air but even as the tailwheel left the ground, 40 knots showed up on the clock. I relaxed just a little and suddenly found myself above the trees moving vertically, indicating 60 knots, which was the top of the white arc and 20 knots above climb speed. At that point, the elevator pressures had disappeared, so I guess the takeoff position marked on the trim indicator is what's needed for climb out. The trim control changes the angle of incidence of the entire stabilizer, which is gigantic, so it’s really effective.

I cranked the 20 degrees of takeoff flaps up and turned downwind to try for a landing. Only then did I realize how tiny a runway looks when it's only 1,000 feet long and two-thirds of it is a narrow slash going through a dense forest. If this was a STOL airplane, we certainly had the place for it. As I reduced power to crank the flaps out, I had to really watch my nose attitude and airspeed, because dropping the nose just a little sent the airspeed sky-rocketing up to 50 knots or more. As I found later, I should have been more worried about getting too fast rather than being afraid of slow speeds.

I turned final at the recommended 35 to 40 knots and saw that I was going to land miles past the point I wanted, so I cranked the rest of the flaps down. I was doing 35 knots, with 400 yards of flaps hanging out, and it wouldn't come down! Finally, it began STOLing and started falling for a point about a third of the way down the strip, right where the runway made a 20-degree dogleg to the left.

I was thinking the Storch had better be as good as everybody says it is, or I'm in big trouble. I turned the corner while flaring and got straightened out just before I hit. The bagel-size tires didn't soak up much shock, but the long oleos sucked up any bounce it had in it, and I nailed the brakes immediately. The gear had touched down right next to the start of a fence, so it was easy to judge how far this mongoose had rolled. I swung around and could hardly believe that the first fence post was less than 100 feet away. The Storch (a name I now revered) had rolled three airplane lengths at the very most and I had been too hot with zero headwind to help.

I must have made at least 15 takeoffs and landings, all of them incredibly short and none of them where I wanted them to be. On takeoff, I soon found that even with the correct trim, I couldn't yank hard enough to come even close to stalling it. As soon as I had a minimum of 35 knots, I could pull back all I wanted and do nothing but climb. I had absolutely no head-wind component and still my initial climb angle was nearly 45 degrees. This is one of the few airplanes around that really will leap off the ground. Taking off three-point in a headwind, I doubt that it would need more than 20 feet to get off, although I was using close to 100 most of the time.

Bagel size tires are mounted on really long stroke oleos. This is about half flap on takeoff. (photo: Stu Gellman)

|

To make short-field landings on a chosen spot, you usually like to get the airplane slow enough so you have to use power to drag it in. I was constantly frustrated in the Storch, because I never got it slow enough to need power. Almost every landing was power-off, and eventually I was so exasperated that I was approaching at 25 knots indicated. At that speed, I needed power to soften the touchdown, but it still wasn't slow enough to hang on the prop. I'll bet the really hot-shoe German types would come creeping in over the trees at practically zero airspeed, letting it fall on command and catching it at the last moment with a burst of power. I tried to stall it while at altitude and found that it not only refuses to stall, but as long as I had the slightest amount of power in to give it elevator effectiveness, I could easily fly the airplane where I wanted while holding the stick all the way back. Once you master that kind of approach, you could land backwards on an outhouse roof.

I had a lot of silly things happen while flying this airplane but the silliest was when I tried slipping it. I was high, per usual, so Ifigured I’d just use a max deflection slip. Hey, it works on other airplanes, why not? As I leaned the aileron into it and got on the opposite rudder everything was going just hunky-dory until I got about half rudder. At that point, the rudder pressure disappeared and the rudder pedal sank to the floor with no effort from me and stayed there. So, there I was, coming down final sideways with a rudder that was stuck to the floor of its own accord. That scared the living hell out of me!

I had to practically stand on the other rudder to get things straighted out. I guess the aerodynamic balance on the rudder is so big that when enough of it catches the wind, it overpowers the surface and yanks it to full deflection. Let’s see you get that one past FAA certification!

Maneuvering in the Storch is a real physical workout. The controls feel the way the airplane looks—gawky and loose. The stick forces are anything but light and to keep it completely coordinated, your feet have to thrash in and out as if you were working an old sewing machine. At one point I realized my T-shirt had worked up in the back exposing the bottom of my spine. By the time I was done flying, I had worn a red spot just above my butt from moving my feet back and forth and rubbing my butt against the metal seat back.

What is it about a Fieseler Storch that appeals to something in all of us? It certainly isn't the Storch's blazing cruise of 70 knots or its 1600-rpm full throttle sound. Nor is it loved for its streamlined gracefulness. Maybe it's the idea of having an airplane that converts your backyard into an airport, or maybe it's the part the Storch has played in history. For me, the Storch has appeal because it doesn't try to be pretty. It's a good honest ugly and doesn't seem to care.

BD