PAGE TWO

|

My first two landings

in the Stampe were in tight formation with Tony Tirri on a

hilly grass strip, but, since everything was happening in slow

motion it was no big deal. |

While I was fastening the five-point British-type shoulder/seat belt,

Tony pointed out everything he thought I should know. "This is

the stick...." There are no brake pedals as such, but when you

hit bottom rudder you get brake on that side. A parking brake handle

is near your left leg, and that's about all there is to it. I asked

Tony what to use on final and he said he didn't know. He said it flew

like a Cub (which I've heard about everything from P-51s to Cubs).

With that, he reached in the front cockpit, the instructor's usual

habitat, and pulled the airstarter handle. The starter surprised

me because it didn't even wind up. The engine was silent one second

and running the next.

The little fold-down doors on either side of the cockpit can

be opened to allow you to lean out to look around the nose while taxiing.

I had the doors closed and still had plenty of airport in sight, as

long as I Sturned occasionally. You sit fairly high

in the cockpit and have good visibility, considering the long nose.

The four short exhaust stacks make the Stampe sound like a mini-P-51.

As I weaved back and forth, feeling a little helpless with the

full-swivel tailwheel, I pulled the two-paned, British-style goggles

down and felt every bit the European aerobatic ace out to trim Count

Aresti's feathers.

The takeoff could be described as a left-hand featherduster. It floated

off the ground as soon as I had the tail up, and I found myself drifting

right. I put in a little left foot, then more, then more. Tony forgot

to tell me the engine turned backwards (or is it ours that turn the

wrong way?). The torque is of no consequence because you leave the

ground so suddenly, but its interesting to find yourself using,

say, the left foot when the cross-wind and slanted runway should call

for the right.

|

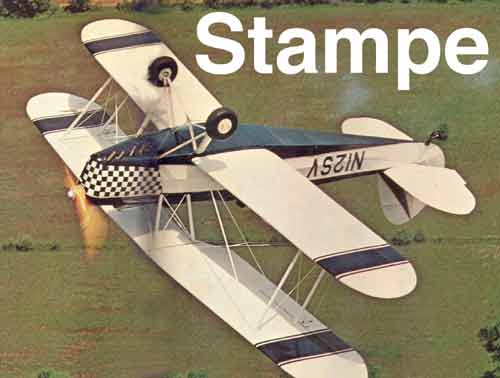

For whatever reason

I think this is pretty . |

The climb to altitude was fun if only because it took place in a nearly

vertical column of air at the end of the runway. The airspeed was in

furlongs per eon or something, so I estimated a nose attitude.

My forward velocity wasn't much more than my upward movement. I was

climbing at around 700 to 800 fpm (a guess), but I was doing it in

one spot.

The controls are beautiful. While the roll rate isn't lightning fast,

like a Pitts, it is certainly all that most pilots need, and the control

pressures are really light. I dropped the nose to get some extra speed,

which demanded I bring the throttle back to stay in the green, and

guessed at a good speed for a roll. Nose up, stick over, feet coming

alive, it arced easily around but the shortage of rudder told me I

had been too slow. The next time, I let the wind noise get a little

louder, the ground went by overhead much more smoothly and the roll

was much more coordinated.

I looped and rolled and snapped then rolled it over on its back to

find it flies better inverted than right side up. The engine coughed

a little in zero G position, but once inverted it hummed along like

a trouper with ME holding very little forward pressure. It did inside

and outside rolling 360-degree turns almost as easily as flying straight

and level.

Tony came up in the other Stampe, and we relived a little bit of World

War I over the fields of Pennsylvania. We then went into a local field

for gas and landed in formation, so my first two landings in the airplane

were in formation with Tony. Normally this would be quite a feat for

me, but we were landing at a walk, so I didn't have to do anything

but follow Tony. In later landings I found it landed as advertised,

just like a Cub, only maybe a little easier.

The feeling the airplane gives while doing anything, from aerobatics

to takeoffs and landings, is one of pure grace. It doesn't depend

on brute force to make it go up, and it doesn't make itself a nuisance

by being either uncomfortable or full of bad habits. It clips along

at something over 110 mph, your head in a near calm behind the faceted

windscreen, and does just what you tell it to. It even tries to smooth

out your mistakes for you. On landing, you have the runway in sight

at all times until you begin to flare, and then it floats until you

get it set up in whatever attitude you want to land in. It's beautiful.

|

It's a pretty basic

panel, but it does the job . |

The folks down at Labate Field are not in the business of building

airplanes, but they are in the business of supplying do-it-yourself

kits for the more energetic among us. All the airframes I looked at

were not only complete, but in fantastically good shape. This looks

like the ideal way to get a biplane. The Renault engine weighs somewhere

in the neighborhood of 350 pounds, so almost any American engine could

be mounted, with the appropriate cowl changes. One fellow in Connecticut

mounted a 200-hp Ranger (along with 40 pounds of lead in the tail),

and it reportedly climbs 1,500 fpm, inverted! Labate says about

half the airplanes they sell end up with 180-hp Lycomings in them,

which should make for a very, very nice airplane.

There is something intangible about the Stampe. The feeling it gives

is hard to describe. It seems to be the perfect combination of a not-too-big

airframe, just-right controls, good aerobatics and easy ground handling.

But it's something more than that. It seems to give you beautiful sunsets,

when it's actually sinking into smog; each runway becomes a never-before-visited

wheat field; each glance at the ground transforms the clustered houses

into virgin countryside. It gives you the romance we've all been looking

for in aviation, and it does so in a way that causes you a minimum

of problems. And above all, it remains a very civilized, very polite

airplane. BD

|