A note from the new millennium: What you’re about read describes

a warbird training situation that in today’s liability and cost-conscious

environment sounds surrealistic and highly improbable. It is, however,

true, and during the 1970’s Junior Burchinal’s school in

Paris, Texas let you walk in, lay down some cash and fly everything from

B-25’s to Mustangs to Bearcats and lots of stuff in between. We’re

talking about actually soloing the airplanes, not just going along for

a ride.

None of his airplanes were prize winners. In fact, some were pretty

ratty and, when we put his Corsair on the cover of Air Progress in

1971, one of the high-buck members of the warbird community was very

upset and challenged me personally and loudly at an airshow.

“How could you put Burchinal’s piece of sh*t Corsair

on the cover and not ours?” He made sure everyone in the crowd heard

his tirade.

I

said, “Will you let me fly your Corsair?”

“Hell, no,” came

the expected answer.

I grinned and said, “Junior will.” And walked away. Some

of the listeners actually applauded.

It was a wildly naïve, unbelievable time that we’ll never

see again. So, read on and welcome back to the dawn of the current

warbird movement.

The big diesel rig rolled off the highway, rooster tails of dust rising

in its wake. It was a normal Texas-style Phillips 66 truck stop, baking

in the sun. The sounds of Merle Haggard snoring through "Okie from

Muskogee"

mingled with the smell of dust and diesels in Nowhere, USA.

But not quite.

The short incoming whistle of a fair of turbochargers began

winding-up, then the Texas afternoon was flattened by a wall of muted

sound that came in lower than the Phillips 66 sign, cleared the wires

and arced up and up—the unmistakable twin-boomed outline of a P-38

Lightning blocking the sun. World War II had come to Texas.

The twin-engine

phantom from the past suddenly quit roaring; gear and flaps flashed in

the sun as it prepared to land. As it curved to the ground, it appeared

to he crashing until I spotted a narrow ribbon of asphalt snaking its

way past the truck stop, over the hill in the general direction of the

38's inevitable crash

|

| Junior flew everything, including his B-25 out of his 30 foot

wide, 2700 foot long strip. The guy had huge cajones and really

good hands! |

The strip was too narrow, too short, but the Lightning reappeared from

behind the hill, its Curtiss electric props ticking over as it taxied

to an unhurried stop, blasting one engine to squeeze between a Wildcat

and a Corsair. The noise stopped completely, leaving only the powerless

unwinding of the props and the mechanical sounds of the canopy coming

open.

The entire scene was unreal. It was as if I'd just stepped

into the "Twilight Zone" and any minute Rod Serling would step

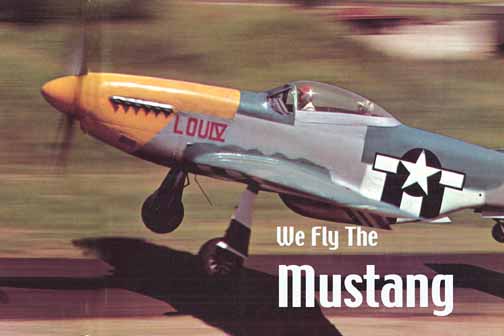

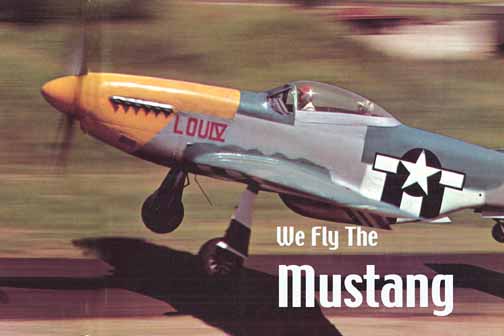

out and give a short introduction. It's unbelievable that on any day

of the week there may be a P-38 or a P-51, or a Corsair, or a hulking

B-25 roaring out of this little duster strip, hurrying on its way, training

students in the fine art of flying warbirds. While there are probably

many aircraft collections bigger, and definitely prettier, the Flying

Tigers Air Museum is undoubtedly the only place in the world where such

a varied bunch of birds roost and work for a living. And they aren't

the pampered hangar queens of some well-heeled collector; they are working

airplanes engaged in teaching the likes of you and me to fly.

The improbable

character who runs this improbable operation goes by the equally unlikely

name of Isaac Newton Burchinal, better known as Junior or Burch—Baptist

preacher, crop-duster, fighter jockey, and eternal devotee of red baseball

caps. Burchinal would be a one man-show even without the airplanes, but

combine his tall Texas Tales with his fabulous assemblage of airplanes

and you have the makings for endless Tailspin Tommy episodes.

You'd expect

a guy doing this kind of thing to have a background replete with hundreds

of combat hours and at least five tallies, then years with the airlines.

Then, finally greying at the temples, he went looking for ways to spend

his free time and money. Nothing could be further from the truth. In

the first place, Burch was in the Coast Guard during World War II, and

never flew in the service—a fact he points

to with some pride when people boast about the martial training it

takes to fly military airplanes.

GO TO PAGE TWO

For lots

more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS. |