PIREP: Bf-108 Taifun

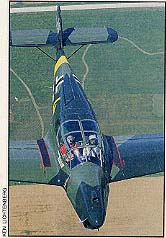

He had spotted me and the late afternoon sun danced down his wings as he rolled quickly into a bank. He was pulling hard, but it would do him no good. I had him nailed. I slid the Messerschmitt's long nose inside his turn and watched his outline drift across the top of the long, mottled brown cowling. In seconds, his outline blossomed and filled the windshield. This was the moment.

Then I saw the shooter kneeling in the open hatch. He was already in firing position and sighting in on me. Too late! I'd forgotten about him. I pressed on anyway. The mission would succeed. Closer, closer until I could see the shooter's face. Then his eyes. He was grinning a typical Amerikaner grin. Damnably confident and smug. He was enjoying my situation. He knew he had me. His face disappeared behind his sights and I knew what came next. I could his finger tighten on the trigger...or was that a shutter?

Jim Koepnick rattled off a half a dozen frames before I heard Bruce Moore's calm voice in my headset urging me to move the Messerschmitt up ten feet and ahead ten feet. Jim continued firing but no flames burst out of my cowling indicating what I knew were most certainly hits. Jim never misses with this personal brand of Canon fire and I knew he was capturing this particular Messerschmitt on film.

I also knew I was enjoying the heck out of this particular shoot. I mean, how often do you get to formate on a Cessna 210 in a Messerschmitt Bf-108? No that's not a typo. It's 108, not 109, and the two Germanic legends are supposedly as close to one another as their designations indicate.

Actually, calling the Bf -108 (or Me-108, both are correct) Taifun a legend might be overstating the case. If contemporary sources can be believed however, the 108 absolutely did give birth to a legend, the better known Bf-109. Incidentally, just to clear up the confusion: Willi Messerschmitt's company, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, was renamed Messerschmitt G.m.b.H in 1936 so both the 108 and 109 were designed as "Bf", but manufactured as "Me." Reportedly, the same year the company was re-named, they narrowed the Taifun's fuselage, moved the pilot to the rear seat location, hung a V-12 up front and voila! A legend was born.

It's unfortunate the 109 has so completely overshadowed the 108, because even in it's day, it was recognized as an outstanding design and age hasn't done much to dim that. The airplane which Bob Lysogorski and his family (sons Michael and Peter and son-in-law Tim Rumrill (SPELLING?)) brought to Oshkosh 97 served to remind us that technological excellence wasn't invented by the MTV generation. In fact, viewing the airplane today, it is difficult to believe the airplane was designed in 1933.

The

fact the Taifun is so technically refined and unique for its age

is no secret. It is a widely held, but difficult to prove, assumption

that the design was a deliberate propaganda attempt to show the

world the Reich's aviation expertise. At the same time, before

the Reich decided to junk the Treaty of Versailles and begin building

military aircraft, the 108 may have been a well-thought out scheme

for completing most of the preliminary design work that could

be carried over to the Bf-109 without raising too many international

eyebrows.

The

fact the Taifun is so technically refined and unique for its age

is no secret. It is a widely held, but difficult to prove, assumption

that the design was a deliberate propaganda attempt to show the

world the Reich's aviation expertise. At the same time, before

the Reich decided to junk the Treaty of Versailles and begin building

military aircraft, the 108 may have been a well-thought out scheme

for completing most of the preliminary design work that could

be carried over to the Bf-109 without raising too many international

eyebrows.

If showing the world the capabilities of the German aviation institution was a goal, it was clearly accomplished. First flown in 1934, the airplane easily captured the (Jack, I don't have the name of the competition or aware) award

As wartime airplanes go, the Taifun has more of an identity crisis than most because of the muddled parentage which is attached to each airplane. Production of the airplane within Germany was suspended sometime in 1942 when it was moved to the captured Nord factory in occupied France, where another 170 airplanes were manufactured under Messerschmitt supervision for the Luftwaffe. Then, the war over, France recognized the Taifun as a great utilitarian airplane and decided they needed some for their own forces. At this point, the parentage of individual airplanes begins to get a little blurred.

In 1946 Europe was still covered with a thick layer of wartime debris. So, rather than beginning immediate Taifun production, Nord simply scoured the country for Taifuns which had been left by the Luftwaffe, as well as collecting as many parts as possible. All of this stuff was, after all free. Ownership was a little fuzzy, but the official former owners, the Luftwaffe, wasn't in a position to argue. Through these spoils of war, France regained a tiny fraction of what they had lost.

They dragged all the airplanes and associated junk to the Nord factory. There they dis-assembled, cleaned and repaired everything, then used the parts to build rebuild those reclaimed airplanes. Then, regardless of where they were originally built, they were registered as Nord 1000's. This point was to prove a minor thorn in the Lysogorskis' side a half century later, when they went to register their aircraft.

Nord also replaced the German 235 hp Argus, inverted, air-cooled V-8 with a 240 hp (US measurement), six cylinder, in-line Renault engine. Where needed, they manufactured new parts to complete the assembly. So, hiding within the airframes officially designated as Nord 1000 may be original German parts, French-built German parts, or French-built French parts. When all the wartime airframes were used up, Nord fired up the production lines and built a small number of new aircraft which were designated Nord 1002's.

The

Lysogorskis worked hard at untangling the foregoing spaghetti-like

production history to establish their airplane's actual pedigree.

In their research, which included talking to both French and Germans

who had worked in producing the airplanes, it became abundantly

clear that in 1946 there was little love lost between the two

nationalities. Understandable. Therefore, when the Taifuns were

put through re-build after the war, everything which spoke of

Germany was removed. They Lysogorski's airplane was used by the

French Navy until 1959 and had probably gone through rework at

least once. At some point, probably while in rework, it had been

registered as a Nord 1002, indicating it was a post war airplane.

Lysogorski, however, found one of the original Nord 1000 data

plates in the wings indicating it was one of the batch of 170

airplanes built for Germans in occupied French. But when?

The

Lysogorskis worked hard at untangling the foregoing spaghetti-like

production history to establish their airplane's actual pedigree.

In their research, which included talking to both French and Germans

who had worked in producing the airplanes, it became abundantly

clear that in 1946 there was little love lost between the two

nationalities. Understandable. Therefore, when the Taifuns were

put through re-build after the war, everything which spoke of

Germany was removed. They Lysogorski's airplane was used by the

French Navy until 1959 and had probably gone through rework at

least once. At some point, probably while in rework, it had been

registered as a Nord 1002, indicating it was a post war airplane.

Lysogorski, however, found one of the original Nord 1000 data

plates in the wings indicating it was one of the batch of 170

airplanes built for Germans in occupied French. But when?

In speaking with several German experts on the airplane, subtleties began to give some answers. Every airplane gets small changes in the course of production and this was the case at the Nord plant. Panel lines and rivet patterns were changed for various reasons. According to those who know, those patterns on Lysogorski's airplane, especially in the tail, indicate it was built sometime in early 1943.

Bureaucracies being what they are however, ("... between Oklahoma City and France, it took me two years and a lawyer to get it registered...") Bob had to accept the Nord 1002 designation. To get it registered in the US. he had to get it de-registered in France first and he could only do that under the Nord 1002 designation. He doesn't like that, but he has an original data plate, the rivet patterns, tailwheel and original Argus connection holes in the firewall to prove otherwise.

Lysogorski has been in aviation most of his life, including long stints as a corporate pilot. During most of that time he'd lusted for a Taifun, but between "...God, country, apple pie, kids in college..." he couldn't afford it.

"I finally decided on my 50th birthday to do something about it. A friend of mine researched every Taifun that had been brought into the country and I went looking for leads. I talked to every owner and found quickly it would cost me my wife, house and everything else, so I decided not to buy one."

After the war Nord

had also built a prior Messerschmitt design that, had it gone

into production, would have been designated ME-208. It was similar

to the Taifun but had a nosewheel. One of those popped up in Lysogorski's

search.

After the war Nord

had also built a prior Messerschmitt design that, had it gone

into production, would have been designated ME-208. It was similar

to the Taifun but had a nosewheel. One of those popped up in Lysogorski's

search.

"I looked at one which was stuffed in a barn and covered with mink manure. My friend with me took me outside and told me, if I bought it, he was going to shoot me it was so bad. I didn't buy it."

Then, after several abortive leads, he stumbled onto a Taifun owner in Pennsylvania who was going through a divorce and said, "Show up with a truck and cash next Thursday and it's yours."

Lysogorski kept his date and had his Taifun. Such as it was.

"The airplane was in what could best be called 'Junk' condition. The magnesium fillets had corroded away and every single nut plate had to be replaced. All wiring, hoses, cables, everything had to go. Fortunately the rest of the airplane had very little corrosion," Bob explains.

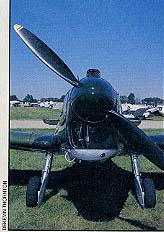

Although he would have liked to put an Argus V-8 in the airplane they were so rare and he would have had to make a cowling, so he stuck with the French engine. Even so, just putting the original Renault back in the air was a challenge.

"There are several versions of this engine," he says. "Some turn clock-wise and some counter clockwise. This one turns clockwise. I had four or five engines for parts, but rings were a real problem. I finally wound up having them made by Niagara Piston Rings. The main bearings are actually poured babbit bearings and a gentlemen in France gave me a set of brand new ones that were poured way back when. We sent the case to Mattituck who align-bored it and magnafluxed all the parts for us. Then my son certified everything and put it back together."

The magnetos were a problem because of their design and the fact one turns right and the other turns left.

Lysogorski

says, "Mattituck rebuilt some Bendix mags and converted one

to turn the other way for us, but I had to make the couplings

myself. The originals were a cogged, hard rubber affair and I

couldn't find rubber that hard or thick. Finally, I was in Rome

and found exactly what I needed. Romanian hockey pucks. Our pucks

are synthetics but those were real rubber. I sat with a file for

about six hours and made the couplings myself. We have 170 hours

on the engine so far, so they must work."

Lysogorski

says, "Mattituck rebuilt some Bendix mags and converted one

to turn the other way for us, but I had to make the couplings

myself. The originals were a cogged, hard rubber affair and I

couldn't find rubber that hard or thick. Finally, I was in Rome

and found exactly what I needed. Romanian hockey pucks. Our pucks

are synthetics but those were real rubber. I sat with a file for

about six hours and made the couplings myself. We have 170 hours

on the engine so far, so they must work."They also had to make mounts for the mags which would allow them to set the timing by rotating the mags because the original French mags had internal timing adjustments.

Even converting to an alternator was a problem because the shaft turned in the wrong direction which would loosen the nut on a normal drive shaft. They had to have one made that turned the other direction.

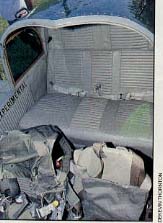

The final Taifun product which the Lysogorski family had on the line at Oshkosh '97 belied the hundreds of little problems which come up in any kind of restoration. In fact, the airplane itself hid many of its most important features. For instance, few observers realized the wings folded. A pin is pulled, a handle is pulled out of the wing itself to use in moving it span wise which disengages the spar attach fitting. Then the wing is rotated leading edge down and folded back parallel to the fuselage. A spring loaded cap in the wing tip is opened and a rod with a hook pulled out which engages a hole in the horizontal tail to stabilize the wing and keep it folded.

The wings also display Handley-Page slates which move in and out independently and are driven by air pressure.

As we fired up (which happens instantly due to the air starter) to taxi out, I was mindful of the airplane's narrow gear which makes the brakes relatively inadequate for their size. They simply don't have enough mechanical advantage when measured against the length of the tail. In fact, I remember a 108 pilot once telling me it was helpful to think of the airplane as a float plane when taxiing in a high wind. He advised "sailing" it using rudder and ailerons as on a float plane to get it to move where you want it. Fortunately, we didn't have much wind, when Bob turned the airplane over to me on the runway.

As

the power came up, that distinctive in-line engine exhaust bark

came back at us as I stared at the edges of the runway. Actually,

although the nose blots out vision to the off side of the airplane,

it tapers so quickly, you can actually see the centerline.

As

the power came up, that distinctive in-line engine exhaust bark

came back at us as I stared at the edges of the runway. Actually,

although the nose blots out vision to the off side of the airplane,

it tapers so quickly, you can actually see the centerline.

As I brought the tail up, I was ignoring everything except keeping it centered. We hadn't talked about takeoff technique and it turns out there actually is one. My usual method of leaving the tail a little low and letting the airplane fly off on its own presented a problem which became almost immediately apparent to Bob. Those long wings fill with lift so quickly, it takes the load off the gear which then starts to extend and we were waddling around, not quite on the ground and not quite flying. Bob solved that by raising the tail more and compressing the struts. Lesson one in Messerschmitt flying: Nail it on the mains until it has takeoff speed.

Once off the ground I decided to leave raising the gear to Bob, as I hadn't been to the gym lately and didn't feel physically up to the task. The gear is raised via a long ratchet handle jutting forward between the seats. It takes 43, 90° yanks on the lever, to get it up and the same number down. While I was letting the speed built to 100 mph, I was conscious of a panting blur on the other side of the airplane that was Bob Lysogorski masquerading as a gear retraction system. There are no separate up or down locks and the direction of gear movement is chosen by twisting the handle grip one way or the other.

I have to admit to loving the way the airplane felt from the second we left the ground (waddling takeoff excepted). For one thing the canopy with all its framing creates a conscious "enclosure" which makes you know you're in a vintage machine, but doesn't get in the way visually. Also, on boarding, the way the doors swing completely forward and out of the way is near genius as it makes the airplane one of the easiest ever to board.

One of the tests for any airplane which reveals some of its subtleties immediately is flying formation with another airplane and that's the very first thing we did. Here I learned to appreciate the airplane even more. Although it's controls weren't as light and quick as many modern sport aircraft, the precision with which they controlled the airplane were impressive. In most flying, we're not aware of how much the airplane is actually moving when we displace the controls because we have no telephone poles or anything else to use in judging our movements. In formation, the other airplane provides that reference. It became easy to slide the airplane two or three feet in any direction at Bruce's commands. I also found I had to anticipate overruns with power a little more because the airplane is so clean. Incidentally the prop is an electric "controllable pitch", not constant speed. You had to set the rpm with an electric pitch control switch to match the manifold pressure you held. It's exactly like older electric props on Bonanza's, etc.

After the photo session, the first thing I did was set up for some stalls. I wanted to see how those slats worked. The first time I didn't find out, because, as I held the nose up burning off speed, the slats slid out and I neither saw nor felt them, they were that smooth. I tried it again, and missed them again. Finally, I had Bob watching to tell me when they started out. They started creeping out about 15 mph ahead of the stall, but even though he was telling me, I absolutely could not tell they were moving. The final stall, dirty was down below 55 mph and was just a mush, with no break. This was impressive for an airplane which cruised at 160 and topped 190 mph.

We messed around with various stability tests and found the airplane to be well within what we would consider "normal" limits for all stability parameters. Many airplanes of the same period have one or more stability characteristics that we'd consider way out of limits today.

The way the airplane handles is very modern, with the closest comparison today being a Beech product. The Taifun has the same slick, relatively light control feel with good response that is characteristic of a straight-tail Bonanza or maybe a T-34. Of course, the Taifun combines that feel with the long, rakish nose, birdcage canopy framing and a general feel that says you're flying something a little different. Something with a ton of character.

One of the interesting aspects of flying the airplane is that the shadows cast by the canopy framing do a lot to make up your impression of the airplane: When the airplane moves, the shadows move. As they snake around the cockpit, never staying in one place, they put your mind in a different place, possibly a different time. This sets off a little adrenaline alarm that makes the flight entirely different than doing exactly the same thing in a Wichita Spam can. Although the airspeed may be exactly the same and the route one you've covered a hundred times, the trip is somehow different when in a cockpit that whispers to you in a voice from long go. In this case, that voice has a guttural, European accent.

We were still over the lake when the tower advised us they were closing the airport in five minutes, so the nose went down, as we raced to close the distance. Power back, Bob became a blur on the other side, and I felt the gear biting into the air and rolled the giant trim wheel forward a few notches. As we arched around to land on the taxiway (180 right), I handed the airplane back to Bob. I didn't feel like making my first Messerschmitt landing on the taxiway with a hundred thousand people watching. Bob nailed it effortlessly on the mains (we had a crosswind) and let the tail down. The flight was over.

We cracked the canopy to get some air and I realized why the airplane had been such a sensation in its time. With only a few modifications, including a steerable tailwheel and better brakes, the Taifun is an airplane that could stand toe-to-toe with anything Wichita or Vero Beach has built in the last 30 years. In fact, in some of its slow speed handling, it is vastly superior to some. Here is a design which is 64 years old that absolutely does not have to hang its hat because of its age.

Bob Lysogorski estimates there are about 27 Taifuns of the various manufactures left of the original 980 built with a little over a half dozen in this country. As a design, the airplane may not be perfect, but there's a lot to be learned from it. It's surprising it has taken us this long to realize that. BD