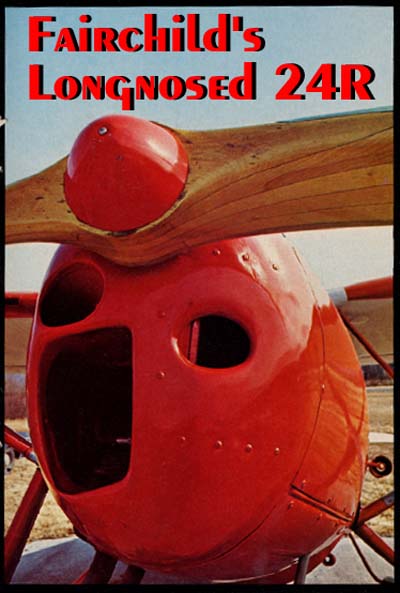

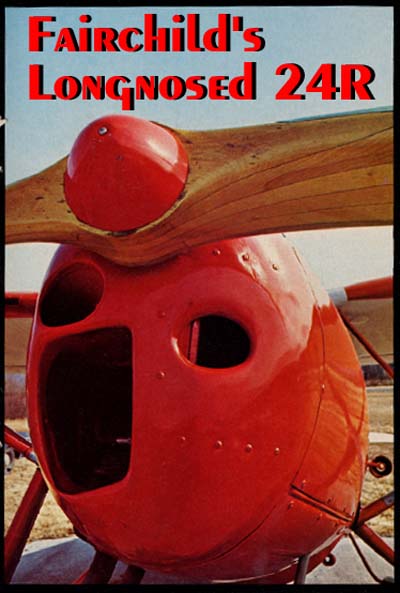

ALL GOOD THINGS come to an end, and the Fairchild Model 24 came to hers in 1946. She really can't gripe though, because thirteen years is a long time for anything to be in production virtually unchanged. The original 1933 24C-8-C used a 145-hp Warner radial and carried three passengers. The next thirteen years saw another seat added in 1937, minor styling changes, and several new engines, but other than that, the 1946 Model 24 was the same as the 1933 model.

With it's outrigger gear and Ranger or Warner powerplant, the F-24 is a ready made antique. A 1946 airplane would usually be called a used aircraft rather than an antique, but a 24R-46 is as "antiquey" looking as anything built in the 1930s, without being so old that termites are eating the steel tubing. The 24 is so plentiful (the military bought over a thousand) and was built so recently that it has become the Model A Ford of the antique airplane crowd.

In many ways the F-24 is really ugly. It's hump-backed, bowlegged, and squats tail down, all of which combines to make it one of the prettiest ugly airplanes around. There's something appealing about the lines and angles in the landing gear, and the multi-faceted windshield. Many antique/classic airplane buffs are definitely turned on by the Fairchild and the Kineyko brothers are in this group.

What ever there is in the F-24 that's ugly, the emphasis is definitely on the pretty in N81204. Wally and Bill Kineyko have owned their F-24 for ten years, the last two of which were spent rebuilding her. They flew it for seven years or so and then decided to make a good thing better. They stripped it down to its underwear, replacing all wood, cleaning and priming the metal, and generally going the whole restoration route. The paint job alone consumed seventy gallons of dope and thinner. This was their first effort at rebuilding flying machines, and every-body agrees that they've definitely succeeded.

Brother Bill got his private ticket in the old bird, but Wally is a product of the USAF, being an ex F-86 jockey. In fact, Wally and N81204 have the distinction of being the ones who turned Richard Bach (world famous writer and executive editor) on to antiques while they flew together in the Air Force.

Constructionwise, the F-24 is typical 1933, with huge pieces of steel tubing running everywhere. There are hangar rumors to the effect that the load factors are in the 10 G neighborhood, and the way it looks, that could be right. One of the best confidence builders in the air-plane is the sewer-pipe-sized piece of tubing that can be seen running through the rear corner of the door cut-out. The entire airplane was designed to be a sod buster on the old grass fields, so it's more than capable of absorbing just about anything 1970 has to give it.

Of course, the thing

that makes the airplane look so much like an artifact is its landing

gear. Each leg pivots at the bottom longeron, and rather than

using a shock cord or strut between the wheels, Fairchild used

a vertical oil/spring strut above the wheel, necessitating the

many angled pieces of streamlined tubing. The tailwheel is steerable

through so many degrees, at which point it kicks out and full

swivels. Even though the gear is wide, Wally says he prefers to

wheel it on when using pavement, but he'll three point it in grass,

where there's more room for error.

Of course, the thing

that makes the airplane look so much like an artifact is its landing

gear. Each leg pivots at the bottom longeron, and rather than

using a shock cord or strut between the wheels, Fairchild used

a vertical oil/spring strut above the wheel, necessitating the

many angled pieces of streamlined tubing. The tailwheel is steerable

through so many degrees, at which point it kicks out and full

swivels. Even though the gear is wide, Wally says he prefers to

wheel it on when using pavement, but he'll three point it in grass,

where there's more room for error.

The Kineyko Fairchild is a 24R-46 and uses a 200-hp Ranger instead of the 165-hp Warner Super Scarab radial in the 24Ws. Being a 1946 model, it was built by Temco in Texas, rather than by Fairchild. The 200-hp Ranger is the same engine used in the Fairchild PT-26, and as a training ship powerplant it was produced by the thousands (government policy: buy one airplane and spares for fifty). For this reason parts are both plentiful and cheap. Trade-a-Plane often lists low time engines for $300-$500, and the engine is extremely easy to work on, making home overhauls feasible (with proper supervision and A&P signature). Since the engine was being produced under wartime conditions and they couldn't afford many rejects, the bearing tolerances were opened up, which accounts for the legendary oil consumption of Rangers. Most of them will burn from 1'h to 2 quarts of oil an hour, but some owners have built up Rangers with tighter bearings and report the oil usage comes down to around a half pint per hour. A high time Ranger does wonders for the petroleum industry!

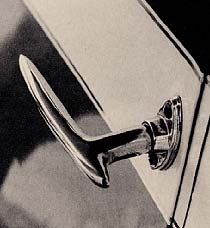

Boarding is classic. You grasp the 1937 Chrysler door handle Wally has installed, and pull the three inch thick door open. Then you hop up on the step pad with the Fairchild emblem cast into it, and climb in like it's a tree house. I felt like the airplane would have been much more complete if it had a front porch.

The first thought that hit my mind, as I settled into the driver's seat, was that my legs had grown about a foot. The rudders are almost even with the panel, so when the seat is adjusted for leg room, the panel is about a block off. I almost had to lean forward to get the mags.

The second impression I got was that the glass in the windshield was an after-thought. It's split into four or five different flat panels, with a wide metal strip joining each piece. To anybody used to the one-piece formed windshields of today, it's like being in a bird cage.

Straight ahead it's

a little on the blind side, but the windshield strips are much

more of a problem than the long skinny nose. Because the nose

tapers so quickly, at least half of the runway is visible (that's

really all you need anyway isn't it?), and the windshield dividers

tend to disappear as you learn to look around/between them.

Straight ahead it's

a little on the blind side, but the windshield strips are much

more of a problem than the long skinny nose. Because the nose

tapers so quickly, at least half of the runway is visible (that's

really all you need anyway isn't it?), and the windshield dividers

tend to disappear as you learn to look around/between them.

The fuel system is unique in that each tank has it's own off-on valve, with no central selector. I asked Wally what happens if both tanks are left on and he said you can get an air lock and kill the engine. Groovy!

Starting is completely conventional, and a fair amount of brake is needed for tight maneuvering, as the tailwheel isn't quite up to the job. I was impressed at how clean the Kineykos kept their air-plane, so I tried to avoid the mud puddles, which took a fair amount of S-turning to see around the nose.

Because of the lack of visibility I turned to check final, and when I saw it was clear, I parked it on the dotted line and got ready to go. I got an okay from Wally and eased the throttle forward, keeping the stick full back until we picked up just a little speed. When I could feel the tail getting light, I moved the stick forward, and the tail came up immediately. As steering was transferred from the tailwheel to the rudder, there was no wandering at all; it felt like the rudder was working long before I lifted the tail. It took the usual amount of close attention and tap dancing on the rudders to keep it tracking straight, then I brought the stick back just a tad aft of neutral and let it fly itself off. So far it felt just like another tail dragger.

Best rate of climb is 80-mph and 2150-rpm, but 90 improves the view a lot. With just two of us aboard and almost full tanks we were getting about 700-fpm, which isn't bad. Wally says his prop is a compromise between cruise and climb, so both suffer, but he's looking for one of the Beech-Roby controllable jobs which should help in both departments.

I leveled off at 3,500

feet, leaving the power at 2150, which is also cruise power. The

airspeed moved up to 110-mph indicated, which two-way runs proved

to be about right. It felt good to be flying a passenger type

bird with a control stick instead of a kiddy-car wheel. The Ranger

mumbled away up front, while I played with the stick, feeling

it out. The controls are surprisingly responsive for such a big

airplane, and I found myself racking it around like a Citabria-which

got a few grins from Wally.

I leveled off at 3,500

feet, leaving the power at 2150, which is also cruise power. The

airspeed moved up to 110-mph indicated, which two-way runs proved

to be about right. It felt good to be flying a passenger type

bird with a control stick instead of a kiddy-car wheel. The Ranger

mumbled away up front, while I played with the stick, feeling

it out. The controls are surprisingly responsive for such a big

airplane, and I found myself racking it around like a Citabria-which

got a few grins from Wally.

I never did get a really good stall. Both straight and level and banked stalls just mushed ahead, exactly like a Cub, the stick clear back and the nose nodding up and down.

Once you get it trimmed up, it just sits there, doing its thing in a straight line, and I felt like something out of an aviation scrap book. It was strangely comfortable, hiding behind all those bars and braces. I looked out through the crank-down side window and through a maze of struts at the countryside slipping by beneath . . . so this is what it was like in the old days. What a grand old way to go places!

The sun was about to desert us, so I turned tail and made it for the field, letting down on the way. Since the grass was still frozen over I had to use the pavement, and heeding Wally's advice I elected to make a wheel landing. Final was made at 80-mph with very little power . . . it's big but it still glides. I kept eighty nailed on the gauge until I started to flare, leveled out at about a foot or so up, and let her settle on the mains, sticking them on with a touch of forward stick. I had concentrated on making sure everything was level and was a little surprised when I felt one wheel touch before the other . . . I was left wing down. The roll-out was fairly uneventful, so long as I kept my head up and my feet working. There was plenty of pavement left, so we went around and I tried it again. I should have quit with the first one, because I touched left main first the second time too . . . oh well.

As big tail draggers go, I was pleasantly surprised at how docile the F-24 was on the ground. This isn't saying it's a 150 or a Cherokee, because it's definitely not, but I don't think a competent Citabria driver should have much trouble transitioning. As with any tail-wheel airplane, its handling problems increase in direct proportion to the amount and direction of the wind; the higher and more crossed it is, the sweatier the whole thing gets.

As compared with some biplanes, the Fairchild 24 could be considered to be a fairly useful airplane. At I10-mph plus, and 10 gallons of 80 octane an hour, it compares favorably with some Wichita sheet iron being produced today. Part of its usefulness is lost, however, because it is placarded against carrying more than 20 gallons of fuel with four people. Wally says he's carried more than that, but the tail drops like a brick on landing. One thing has to be said for the Fairchild 24: it's about ten times more comfortable than anything in production today-sort of like flying your living room.

I've often thought about how we've changed our ideas of traveling to the point where many pilots just want to get there-as fast as possible or faster. It's a shame, because flying isn't a destination, it's a means with no particular end, and floating around in this latter day antique made me once more aware of that fact . . . fast enough to be useful, but slow enough, and with enough charm, to keep the sky in its proper perspective. The Fairchild 24 is the best way I know of to turn the pages back to when flying was still flying. BD