PAGE TWO

|

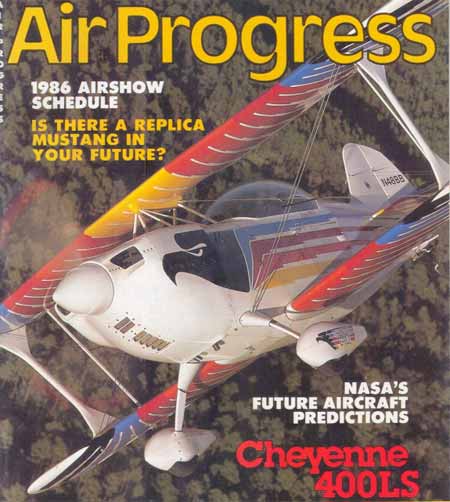

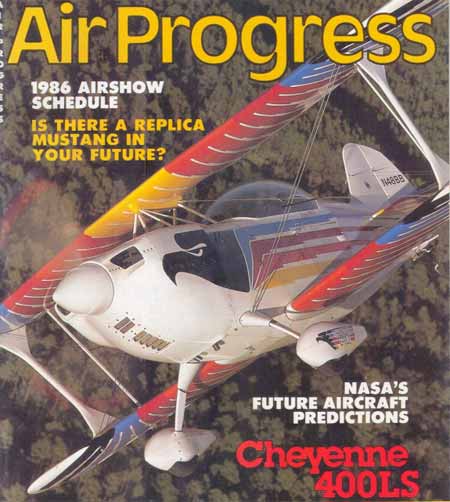

| The standard Eagle paint scheme has to be one

of the most involved every attempted on a homebuilt biplane but

they don't look the same painted any other way. |

Structurally a Christen Eagle uses concepts that are as old as aviation.

The fuselage is a welded steel tube truss mated to wooden fabric-covered

wings using build-up, truss type ribs. Possibly the only divergence

from tried-and-true biplane tradition is the use of a spring steel

gear.

Certainly some of the most obvious differences between the Eagle and

the two-place Pitts are the wider fuselage (newer Pitts are also wider),

the spring steel gear, the general cowling configuration, the canopy

and the fact that there is no rear instrument panel . . . the pilot

looks over the passenger's shoulder at the front panel.

Even though the Chirsten Eagle is the Heathkit of homebuilt airplanes

it is still a gigantic project. Many corners have been cut for the

builder and hundreds and thousands of hours have been saved but to

complete the airplane to the standards expected will still take approximately

1500 hours and maybe 2000, with much of this being spent in the finishing

phases. By the way, the complex masking which always accompanies paint

jobs like those on Eagles is greatly simplified by the ingenious use

of die-cut masks which are part of the kit. This explains why so many

Eagles have nearly identical paint jobs.

Regardless of the obvious similarities/differences between the Eagle

and the Pitts, it is only by strapping one on that you find the true

differences which, surprisingly enough, are many.

I trundled down toAero Sport in St. Augustine, Florida where Jack Cheek

graciously loaned me his Eagle for my first Eagle ride. Having owned

an S-2A Pitts for fourteen years, I was naturally eager to see how the

two stacked up. I was also aware that having owned the Pitts for so

long, I was going to have a hard time being partial.

THE SECOND I CLIMBED INTO THE SADDLE THE differences began to

hit me in the nose, or more accurately, in the butt. The wide, plush

seat and general cockpit furnishings are a far cry from the Pitts spartan

way of doing things. Everything is finely fitted and perfectly positioned

for comfort and ease of use. This is all in direct contradiction to

the Pitts that bears a striking resemblance to a WWII submarine in

the way that all the airplane's innards are hanging out and constantly

poking at you. Also, you'll never hear the word "comfort" associated

with the flight deck of an S-2A Pitts, unless it's one of the very

last ones that incorporate a lot of Eagle mods. The normal Pitts' cockpit

is flat crude when compared to an Eagle's.

If I was impressed about anything connected with the Eagle's cockpit,

it would have to be the canopy. When I pulled it shut, it seemed to

disappear. The glass just "went away" because it was so optically

perfect!

Taxiing out, I got my first serious surprise about the Eagle. On the

ground you can't see any more out of it than you can the Pitts. With

the metal cockpit combing of the Pitts replaced by glass that went

down to the longerons, I expected to have greenhouse visibility. No

way! It was difficult to figure out where the visibility

went, but my guess would be that the wider fuselage did it. At any

rate, the Eagle is not an airplane you taxi straight down the centerline.

A little zig-zagging is in order to clear traffic, potholes and departing

turtles.

Out on the runway, I lined up so the edges of the pavement were equally

visible on both sides and started feeding the Lycoming some 100LL.

I was impressed by the electric motor smoothness of the engine, as

it worked its way up to full pitch. The Pitts would be barking its

head off at that point, leaving absolutely no doubt in your mind that

you have a four cylinder shotgun going off outside the airplane and

between your feet.

True to hot biplane tradition, the Eagle started rocketing down the

runway and I could feel the spring steel gear waffling back and forth

a little as I picked up the tail. The Pitts' gear is just the opposite:

It is so stiff that the airplane skips and skittles along, just hitting

the high points on the runway. The Eagle gave me a boulevard ride until

it got light on its feet and went flying before I gave the stick the

tweak the Pitts requires to break ground cleanly. In that respect the

Pitts seems heavier.

One thing is certain, when climbing away from the runway, even with

two people on board, an Eagle is no sluggard. Sixty seconds after brake

release we went through 1500 feet and I was at least 10 mph over best

rate of climb speed. In that area the Eagle is at least as good as

the Pitts.

With 3000 feet between me and the inland water-way below, I dropped

the nose and watched as the speed immediately jumped to 140 mph. Bringing

the nose up, I fed in the ailerons and watched as Florida cartwheeled

around the spinner in an aileron roll. Then another. And another. And

on and on.

I started getting serious and made some of the slow rolls into 20-30

second affairs, finding out I had to work a little harder than usual

because the Eagle seems more rudder sensitive than the Pitts and doesn't

groove through the roll quite as easily. I had to cross control a little

longer past inverted and then transition to the other rudder a little

harder. All the time I was rolling, I could feel the tail trying to

move, telling me I was slipping and sliding. These traits are neither

good nor bad, but I hadn't expected the differences to be so pronounced.

In loops I couldn't find any appreciable difference between the two,

although the Eagle does seem to pick up speed going down hill a lot

faster. This isn't surprising considering how much cleaner

it is than my faithful old beer-bellied biplane.

Rolling over on my back, I had the distinct impression of

having to push the nose a little harder to make sure the altimeter

didn't start unwinding. The Eagle is just like the Pitts, it doesn't

know upside down from right side up, but I found myself having to keep

my head about me because I didn't really have a set of references worked

out and was holding altitude on this initial try by instruments.

ROLLING RIGHT SIDE UP AND SLOWING TO 115 with the nose slightly high,

I yanked the stick back and into the corner, at the same time stomping

the right rudder to the floor. Barn! The airplane responded

by instantly stalling and whipping around its axis in a snap roll.

As we went around I could feel the tail moving around behind me, buffeting

as though the elevator was trying to stall. A lot of airplanes do that

and they generally require initiating the maneuver with a lot of elevator

but immediately backing off just a little to keep the tail flying and

holding the wings stalled. The Eagle was one of those. The Pitts requires

you to lead slightly with the rudder and all but refuses to snap to

the left and it takes a lot of technique to make them clean. The Eagle

needs technique too but it's a shade different. Also the

Eagle seems to go around a little slower, but is still lightning fast.

I'm certain that with enough banging around, I'd learn how to blow

in the Eagle's ear and she'd snap like a tiger. My initial impression

was that the Pitts has a cleaner and quicker snap, but only after you've

mastered the stomp-and-yank technique.

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|