|

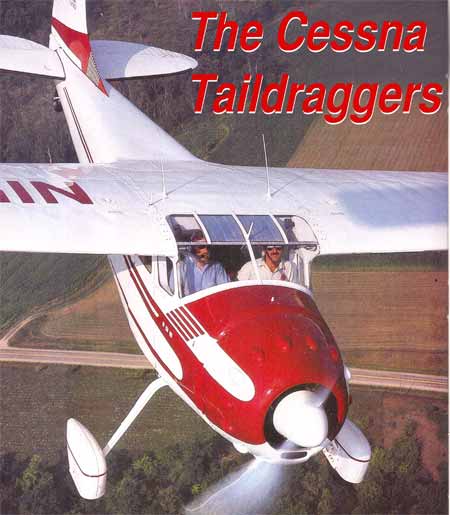

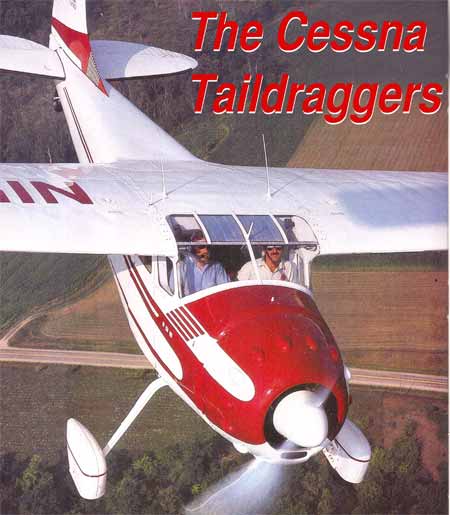

Flying the Cessna Taildraggers |

Cessna Built a

Bunch of Tailwheel Airplanes and we Review Them All |

PAGE FOUR

C-180 The C-180 was produced until 1981 — at which time the total changes from day one were minor. The empty weight climbed 150 pounds to 1701, while the useful load went up 100 pounds to 1100. After the first few years, the engine was standardized at 230 hp and fuel options went as high as 84 gallons, giving the airplane incredibly long legs. Standard tankage was about 55 gallons and the airplane eventually got an option for six seats. The original C-180s cruised at 157 mph and the last at 162, although the stall did decrease from 59 mph to 54 mph. None of these figures are even worth worrying about, since individual airplanes were on either side of any of these numbers. In terms of flying, the C-180 set new standards for utility airplanes and was the favorite on floats. There are probably more C-180s in the north country than any other single airplane. The plane is also the favorite for jungle bush pilots working rough, short runways. The C-180 is not a Piper Cub, especially when fully loaded and with full flaps, but it is also not a particularly demanding airplane. If there is a handling problem it is getting pilots used to the spring gear and the way — if the pilot is asleep — it will bounce a crow hop. For the most part, the 180 is simply an airplane that asks you to land with a certain amount of care.

C-185 There's a general misconception that the C-185 is bigger than the C-180, but this is not the case and it just appears that way be-cause of the longer windows. In actuality, the specs show the C-185 to be nearly a foot shorter with exactly the same wingspan. The 300 horses, as would be expected, make the airplane a spectacular performer as well as increasing utility. Useful load goes up to nearly 1600 pounds, but this fact doesn't give away any of the plane's short-field capabilities. When lightly-loaded, these things are second cousin to a helicopter!

C-190/195 The five-place airplane seats three across in the back, while the front two are separated by a sizable aisle used for getting up to the flight deck. Once in the driver's seat, many pilots are initially bothered by what appears to be a total lack of visibility. This is strictly a perception problem since, by moving against the side of the cabin, the pilot will see that the nose slopes away fast enough so he can actually see the center-line of the runway 50-75 feet out in front. However, when looking off to the right the world simply doesn't exist. The airplane is so wide there is not way of knowing what's out on the right without exaggerated "S" turns. That's why many pilots have a convex mirror mounted above the passenger's head to aid in watching for fuel trucks, airplanes, and buildings of less than three stories. Once the tail is up, the world comes back into view, and in flight the nose ceases to exist. Turn your head to the side, and you are looking right into a wing root, but this is another perception to be overcome. In a turn, the pilot can see entirely over the wing because the windshield wraps back over his head, which, unfortunately, is also a source of sun glare and heat. The C-195 is a real pilot's airplane — delightful in the air and on the ground, it asks only that you keep it straight. Actually, the 195 doesn't ask, it demands. The results of letting a C-195 get crossed up on landing are almost always expensive. Because the airplane is so big and the gear so flexible, a ground loop usually results in folding a gear leg, destroying a gearbox,and folding a wingtip. Fortunately, the airplane is not difficult to keep straight, but it is absolutely essential the brakes and tail-wheel steering be kept in top condition. Many aircraft have been damaged simply because the steering mechanism got worn and locked up momentarily one way or the other. The airframe was equipped with four basic engines. The smallest was the 240 horse Continental and with this engine the design was designated C-190. Here's a piece of Cessna trivia for you: The cowl bumps on C-190s are riveted in place from the inside, but on 195s they are riveted on the outside. Guess they needed that additional 1/16 inch of clearance. C-195s all have Jacobs engines of various horsepower. The most common are the 245 and 275 horse radials with an occasional 300 hp. The military put 330 horse Jakes in their UC-126s but these are seldom seen. The 275 hp is probably the best of the bunch. Page has an STC for a 350 hp turbo-charged Jake that lets the airplane really get up and haul at altitude. Jacobs are fine engines as long as it is understood they are going to leak — sometimes a lot, sometimes just a little. Jacobs leak oil and that's a fact of life. Jakes are also unique in having a magneto on one side and a battery-powered, automotive-type distributor on the other. The system works great, so don't worry. At 3500 pounds gross, the C-195 is no featherweight. The plane has a useful load of about 1300 pounds, but few operators paid attention to that number. If they could get an item in the door, they flew with it. The airplane has prodigious weight-lifting capabilities, especially with the bigger engines, but is no speed demon. Most 195s can be counted on for 155-165 mph cruise, but that is in limousine splendor. No modem airplane offers the same accommodations or solid feel. The C-195 is the hands-down winner for the best-looking tailwheel Cessna ever built, as well as encompassing all the finer points of utility, fun, and funkiness. SUMMARY There is a Cessna tailwheel for every taste, every need, every pocketbook. And there are lots of them out there, so start beating the bushes before they all wind up in Europe. Those Europeans recognize a good deal when they see one. BD

|