Text & Photos by Budd Davisson, Flight Journal , Oct 1997

Bill and Claudia Allan are not only friends, but I consider them

to be curators of some very important pieces of aviation history.

Their aircraft are among the finest examples of the type in the world,

but their collection of artifacts and memorabilia are matched by

few, if any, museums in the world. It is because of them, and people

like them, that aviation history will remain intact for future generations. |

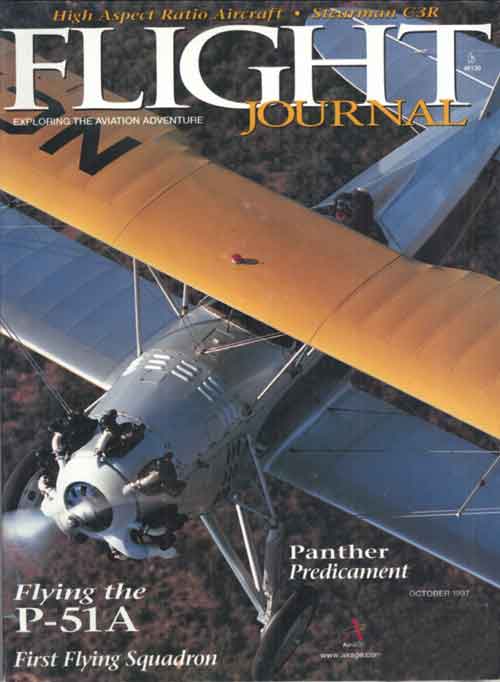

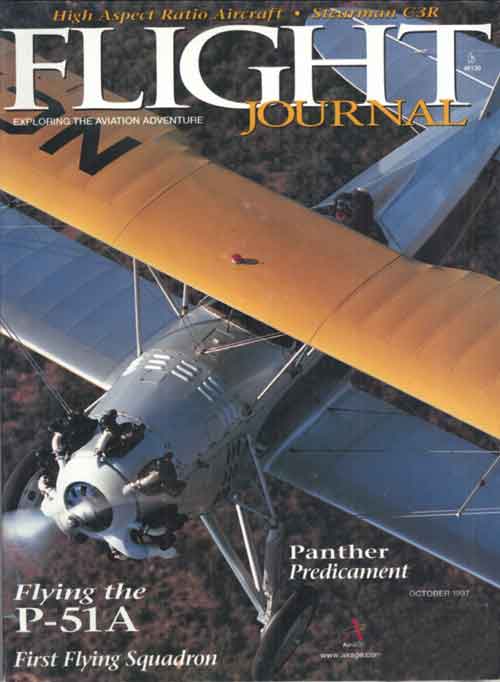

Stearman C3R Impressions of a Different Age The crank protruded from the cowling over my head. I wrapped both hands around the handle and on the first downward pull, a subtle sound, somewhere between a low rumble and a reluctant whine, escaped the fuselage by my right shoulder. The flywheel didn't want to be disturbed. Inertia starters being what they are, the first several turns of the crank violate Isaac's law of inertia: Things at rest want to stay at rest.

The crank crested on its own and all my weight went into the next pull. The whine grew higher in pitch. The crank became slightly easier to turn and crested more quickly. Another pull and the pitch climbed. In a matter of seconds, the pulls were coming faster and easier, both arms and hands working to stay ahead of the flywheel. We had violated the first rule and were building on the second, as the whine became a high, thin, mechanical keening: Things in motion tend to stay in motion. I lost track of the number of turns, but when the scream would go no higher, I yanked the crank out of its coupling and walked to the wing tip. The thundering of my heart and breath were in synch with the screaming flywheel. Bill Allen's voice from the cockpit called, "Clear." In an instant the mechanical scream dropped to a throaty growl as the built-up inertia was slammed through a clutch and into the Wright J-6 engine. The prop turned. Jerking at first, then in an easy, halting dance until the fuel-air mixture being sucked into the cylinders was right. First one jug fired. The puff of smoke signaled possible success. Then the hollow coughs came closer together, eventually blending into that wonderful sound which only radial engines make. I was being treated to the original soundtrack that had been background to an important, transitional era of aviation. The period was a coming-of-age which saw airmail, passenger and executive transportation step from the pioneering days of the twenties to the golden age of runaway aviation development in the thirties.

Bill Allen was orchestrating that sound track as well as offering me a chance to see that age from a unique vantage point: The front cockpit of his 1930 Stearman C3R. Allen and his wife, Claudia, are among that rare group of individuals who have such a feeling for the past that it shapes their present and their future. Equally as important, they have the wherewithal and dedication to do something about that feeling. The Allens' life together is a search for a better, more viable way to do their part in preserving the art and the artifacts of aviation's past. To that end, their hangar/apartment complex on Gillespie Field in San Diego has to be viewed as far more than the heart-stopping collection of memorabilia and aircraft that it is. Yes, letters from Lindbergh while still an airmail pilot share a display case with Roscoe Turner's pass to the National Air Races. And yes, a massive collection of helmets and goggles is almost lost among cases displaying unreal artifacts from 1900 to today. And yes that is Louise Thaden's original race-winning Travel Air over there behind the Allens' Ryan STM, the Great Lakes and the PT-22. What the artifacts actually represent, however, is the couple's unbounded energy and drive to throw their arms around history and protect it. An even better gage of that energy is what Bill sees as one of his more concrete efforts to "...give back to aviation as much as it has given me...." He and a friend, Carl Hayes, worked with state legislators to get antique aircraft reclassified in the state of California so personal property taxes would not apply. It made no sense to them that restorers could take a pile of useless junk in which the State saw no value, invest a huge amount of their own time and money, only to have the State tax it. Allen and Hayes apparently proved their point.

The Stearman, which was restored by Garth Carrier for its last owner, Jeff Robinson, is one of the centerpieces of the Allen Airways collection. It is far from the "Stearman" which many visualize when the name is mentioned. In fact, the so-called Stearman of WWII fame, isn't even a Stearman, as most were built by Boeing aircraft. The Allen's C3R comes from a different age and was built for a different purpose. The last half of the 1920's, the era of the Stearman's birth, was an interesting period. The first half of that decade had been spent recovering from a war and playing with cheap, almost free, surplus aircraft. Aviation's leaders recognized, however, that they couldn't continue to base their future on what had seemed to be an endless supply of surplus OX-5 engines. Also, the engine's short comings were all too obvious. This, coupled with the building profit potential of the airmail routes being offered civilian contractors demanded better, more reliable power plants. In a matter of only a few short years, a gigantic leap in engine technology gave the industry a wide range of engines of unheard of reliability and longevity. An OX-5 was lucky to live 75 hours before needing an overhaul. The new generation of engines boasted of 500 hours and more, with fewer, if any, forced landings in-between. With the new Wright and then Pratt and Whitney engines available, new airframes took form. Lloyd Stearman was one of those at the forefront of aeronautical development. In his first efforts, Stearman designed nothing that was revolutionary. In fact, his entire line of aircraft prior to being absorbed into Boeing was mostly evolutionary; one airframe continually tweaked and twisted to meet a new market or need. Bill Allen's C3R was one of those evolutionary steps. The C3 series of biplanes was typical period Stearman: A simple airframe laid out in such a way that it was easy to maintain, strong and efficient. Those were design hallmarks of all Stearmans. Originally, the airframe had been aimed at the utilitarian aspects of aviation which were only then being discovered by Americans of all varieties. With the specter of impending engine failure pushed further into the background, more Americans were willing to trust these new fangled machines to carry mail, cargo and themselves at unheard of speeds approaching 100 mph. To a dirt-road nation driving Model A Fords, that kind of performance was the stuff of which science fiction was made. The earlier C3B could carry a solid 600 pounds of pilot and cargo in addition to its full load of fuel. This made it a truly useful tool that could carry any combination of items across America's ever expanding horizons. As more and more companies began building airplanes around the new engines, the competition became more fierce and Stearman began looking around at new markets. The C3R was the result of that search.

Stearman called his new C3R the "Business Sportster" a name which clearly identified who he was trying to bring into the Stearman fold. With the new J-6-7 Wright engine of 225 hp, the airplane offered the ability to easily carry two passengers in the front seat at 105 mph for nearly 500 miles. Stearman designers took the basic C3B utilitarian airplane and added niceties which would appeal to the sportsman pilot as well as the operator seeking to use the airplane for charter. The head rest behind the pilot, for example, increased his comfort level as the luxurious upholstery in the front pit did for his two passengers. However, the front cockpit was only 33 inches wide, so, if the passengers weren't well acquainted before their flight, they certainly would be before it was over. As I scrambled up the wing walk against the idling prop blast and reached inside to unlock the small side door, I wasn't thinking of comfort and efficiency. I was only thinking what a rare opportunity this was. Climbing up on the nearly waist high wing had been easy: Stearman designers had placed the fuselage steps perfectly and sliding into the cavernous front seat through the side door was simple without having to step over a cockpit side. Once inside, however, I could see where forward visibility for the passengers hadn't been a primary design goal. For increased comfort, they sit well down in the fuselage on a broad bench seat, with the top edge of the cockpit combing at eye level. Even in flight, passengers had to look between the cylinders to see straight ahead. The pilot, however, sits high and in a narrowing cockpit which gives much better visibility. Even so, as with all serious taildraggers, visibility ahead was non-existent on the ground, so our path to the runway was a series of lazy "S" turns for intermittent clearing of the taxiway.

Even taxiing out, the cockpit smelled of aviation. Hot engine metal, an occasional fleck of oil hitting the windscreen, the easy feel of the 30 inch tires and long stroke out-rigger landing gear reducing the taxiway to the texture of velvet. The period of its birth was alive in this airplane's bones. Lined up on the runway, all I could see were the very edges of the asphalt, which isn't uncommon with this vintage of flying machine. I knew Bill could see more from the back seat, but not much more. As the power came up, the old Wright leisurely wound its way up to 1,600 rpm and the big Hamilton-Standard ground adjustable prop dragged us down the runway. It wasn't accelerating so much as it was breaking into a slow, rumbling trot. When the rumbling stopped, it meant the airplane had left the ground. We were doing somewhere around 60 mph at the time. Maybe less. The airplane didn't really seem to care how fast it was going. If it was flying, it was fast enough. My goggles were superfluous as there was little or no wind in the cockpit and even leaning to the side produced no slipstream. As we leveled out, however and speed creapt up to 100 mph, I had only to stretch a little to feel the wind playing with the top of my helmet. As he turned the controls over to me, I began to let the airplane tell me what it thought about this new fangled notion of aviating. For one thing, as I tested controls, going bank to bank, pumping the rudder, and generally getting to know it, the Stearman told me it wasn't nearly as stodgy as some would think. It was certainly more ready to dance than many of its peer group. Judged against today's light aircraft, its roll rate and control response would be viewed as ponderous. Slow. Ungainly. But that is an arrogant viewpoint nearly three-quarters of a century removed. Different standards must be applied to the breed which the Stearman represents. Compared to many of the WACO's and Travel Airs of the day, it is surprisingly agile. Put it against something like a Fledgling or Commandaire, and it comes off as positively nimble. On landing it was apparent it helped to know the geography of the airport because a longish final approach is guided by land marks, not the runway. The runway is totally invisible somewhere ahead of the airplane. Because the airplane has the drag coefficient of a tumble weed, there was no reason to begin slowing down well away from the airport, as with most airplanes. The power is reduced just enough to let the airplane come down. When the edges of the runway magically appear in the peripheral vision, the power is brought back, the airplane held off the runway, as the speed rapidly bleeds off. Eventually, the airplane gives an audible sigh as the wind goes out of the wings and it settles on to its cushy gear. We are moving at a fast trot again and the flight is over.

When viewing the Allen Airways collection there's a real tendency to envy. To covet. In reality what we should all be doing is thanking the Allen's for doing what we can't do. They are saving something of the past for the future to enjoy. Much more important, they go out of their way to share and make it available to others. Sidebar: A Classic's Journey It is miraculous that a larger-than-average, but fragile as an egg, mechanical anachronism such as Bill Allen's C3R has survived. Time and the let's-clean-up-the-airport crowd caused thousands of such flying machines to meet an ignoble end in a bonfire or scrap drive. This is especially true of the big biplanes of the period of the car's birth. Technology changed so rapidly immediately after Allen's Stearman rolled off the assembly line that the concept of an open cockpit executive transport seemed ludicrous by 1940. What had been designed for a developing trade with the soon-to-be biz jet crowd, was, in a matter of a few years, relegated to the far corners of airports as utility hacks.

NC794H was luckier than most. Its first ten years saw it cruising the East Coast, becoming used less and less as more modern aircraft encroached on its purpose in life. As WWII bore down on the US, 94H escaped the scrap drives by giving up its executive position in life and becoming a blue collar worker as a crop duster. With increasingly larger engines, it was the Stearman's innate ability to carry big loads at slow speeds which gave it a utility factor out of proportion with its age and kept it off the scrap heap. 94H earned its keep with its wheels in the cotton until being disassembled for dead storage sometime in the late 1940's. It went through more than ten more owners over the next 37 years before coming to rest at Early Motors, Inc., as Jeff Robinson calls his Arletta, California based airplane collection. At that point NC794H was no longer viewed as a nearly useless old airplane. The age of the antique airplane was in full bloom and the old Stearman was once again revered. Unfortunately, its years as a duster had stripped it of just about everything except its dignity. Robinson had Garth Carrier spend 18 months full time restoring the airplane using as many original parts as could be found. Where they couldn't be found, they were fabricated. No concessions were made to modern times other than a tail wheel in place of the skid. The final result was an airplane as original as Carrier could make it. Bill Allen added the airplane, one of only four or five C3Rs in the country, to his collection in 1990 and has flown it "...something over 200 hours..." since. That's a lot of flying for such a prestigious old bird and includes flights to most of the major fly-ins in the Southwest. Bill and Claudia Allen understand and respect the responsibility that comes with owning such a piece of history. Its not a rich man's toy but an artifact to be preserved, appreciated and shared.

|