It has been several weeks since I pushed the throttle

home on that big Pratt & Whitney R-2800, and I've flown a lot of

airplanes since, but I can't get that Bearcat out of my mind. I'll

be in the middle of an exciting conversation, and suddenly

my mind will shift gears, the lights go dim, and that tiny windscreen

pops up in front of me. I'm once again strapped in that miniscule Plexiglas

bubble, surrounded by a maximum of noise and a minimum of airplane.

As I blink my eyes, unbelievingly, my right hand unconsciously

twitches and the Texas horizon rotates in an effortless slow roll.

(Ed Note from 2008: now, 30-some years later,

the airplane still has the same effect on me.)

|

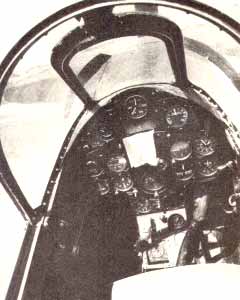

The cockpit is not only form-fitting

but they put the controls, like gear, etc., right where you can

easily find them. |

Pilots may fly a Bearcat and not like it, and others may be indifferent,

but none of them will ever forget it. There are airplanes that do better

aerobatics, and others that get off shorter, and certainly some are

more comfortable, but there is only one airplane that mixes all these

ingredients together using raw horsepower as glue—that's Grumman's

fantastic Bearcat.

When Grumman builds a fighter, they don't mess around. The Bearcat

was the last of a 20-year string of successful prop-driven Navy fighters,

and they stuffed every little trick they knew into it. The design philosophy

for the Bearcat was simple: Get all the power you can into

the smallest airframe possible and still design it so it's a cinch

to land on a carrier.

I'm sure the Grumman engineers were a little disappointed when they

didn't get to see how their aluminum assassin stacked up against the

competition. By the time the F8F was all packaged and ready for operational

use, the War was over and the scream of turbojets began drowning out

that lovely sound of P&Ws. Only 1,266 Bearcats were built and most

of them were given to the French and Thai air forces. Supposedly, only

63 were released to the surplus market, which accounts for the small

number—around 16—that still exist in the United States.

Because of the airplane's short tour of duty, there are few ex-military

pilots who got to play with them at the taxpayers' expense, and there

are even fewer taxpayers who have gotten to shove that throttle to

the stop. About the only way you can fly a Bearcat, short of buying

one, is to go through Junior Burchinal's warbird school in Paris, Texas.

His Bearcat is the one with which Mira Slovak won the 1964 Reno Air

Race. Junior uses it for airshow work as well as for giving the ultimate

thrill to those who dare to hop aboard.

When I first saw her, she was next to her racing opposition,

the Mustang. There they were—one sleek, long and streamlined;

the other looking like a bullfrog trying to stand on tiptoes. They

were both intended to do basically the same thing, but their designers

took different approaches. North American decided to go for the cleanest

airframe possible so they could get maximum performance with a medium-size

engine. The Grumman gremlins decided they'd take the healthiest engine

available, strap a pilot to the accessory section and then

try to economize on aluminum.

The big prop presented an interesting problem for the Bearcat designers.

Where would they mount the gear? If it were long enough to keep the

prop out of the asphalt, it would have to be mounted just inboard of

the navigation lights to keep the wheels from touching each other when

retracted. They came up with a clever solution in articulated, two-piece

gear legs. The legs fold in two places, one at the normal position

at the wing, and the other more than a foot down the leg. This way,

when the gear is retracted, the upper portion goes out and the bottom

comes in.

After climbing up the spring-loaded steps chiseled into the fuselage,

you open the canopy by reaching inside a little trap door in the fuselage

and using the cockpit hand crank. Once inside, you know you've strapped

on a real performer. The first indication of its get-up-and-go is the

little window on the airspeed indicator that says, "Mach." Mach?

That all-important gauge is at the top of the panel where you can't

possibly miss it.

This is probably one of the smallest fighter cockpits around, at least

compared with the few American fighters I've sat in. A big man would

have to be a hunchback to clear the canopy. It isn't necessarily cramped,

but it definitely has that tailored-to-fit feel. Also, it's one of

the best finished cockpits the U.S. ever put behind a propeller. A

lot of the WW-II birds, especially Navy types, look as if they were

designed by the same guy who plans the plumbing in sub-way tunnels,

because tubes and wires and fittings usually stick out all over the

place. After all, they weren't supposed to look pretty. The Bearcat,

on the other hand, has none of the Spartan, stark look. The wires are

enclosed in consoles on both sides of the cockpit that bend up gracefully

to meet the panel.

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|