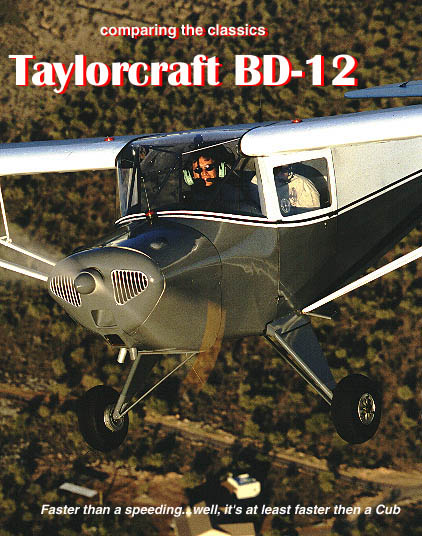

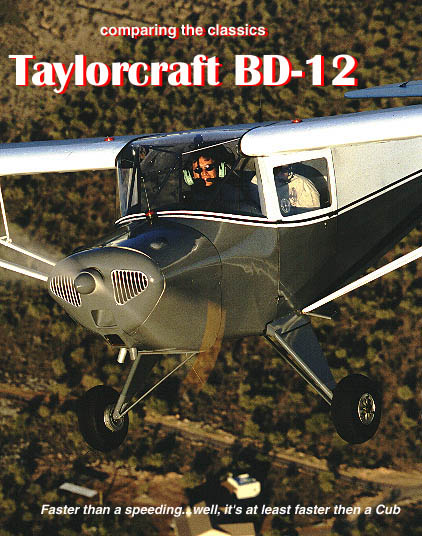

Classic Comparison

Taylorcraft BC-12D

You can almost guess how long an individual has been aware of classics of the late 1940's by the amount of awe in his or her voice when seeing a pristine, restored BC-12 Taylorcraft. The reason for that is the image many carry in their minds of a Taylorcraft is of it sitting lop sided on the back tie down line, one tire flat, a bird-nest apartment in the cowling and mice running up and down inside the rotting fabric. Cubs and Champs never slid down hill as quickly as did the Taylorcraft breed. Even though every pilot on the airport recognized that Taylorcrafts were far faster than the rest of the 65 hp group (with the possible exception of 8A Luscombes), the airport hobo was most likely to be a Taylorcraft.

There's no good explanation for the Taylorcrafts past image except that there were just so many of them around, some were bound to go down hill. Although never produced in the same numbers as the Cub, as soon as old C. G. Taylor introduced his side by side Model A in 1937, the market forced him to crank them out like cookies. It wasn't unusual for the factory to be doing 30 airplanes a month in 1938 before the depression had even wound down.

The Model A's had

the less then overwhelming A-40 Continental, but it performed

so well, every one loved them. Then came the first of the overhead

valve Continentals, the A-50 (Taylorcraft Model BC) and then a

shining knight came riding over the horizon in the form of the

Continental A-65. The A-65, more any other single technological

event, made the Taylorcraft and every other of its peer group

take a giant step forward. What had been a good airplane became

astoundingly good.

The Model A's had

the less then overwhelming A-40 Continental, but it performed

so well, every one loved them. Then came the first of the overhead

valve Continentals, the A-50 (Taylorcraft Model BC) and then a

shining knight came riding over the horizon in the form of the

Continental A-65. The A-65, more any other single technological

event, made the Taylorcraft and every other of its peer group

take a giant step forward. What had been a good airplane became

astoundingly good.

C. G. Taylor had an eye for building clean, low drag airframes. He got his lift from lots of wing and his speed from low drag. On the same engine with which a Cub could barely make 80 mph, the BC-12 series was easily doing 95 mph and some would touch 100 mph.

Taylor built thousands of airplanes before the war shut him down to start making L-2's. After the war, they cleaned up the airplanes still further and introduced the BC-12D. There are probably more of this model existing than any other. By the same token, more BC-12D's died on back tie-down lines than any other given type. Go figure!

Mechanical Description

Considering that it was built to beat the Cub and humiliate C.

G. Taylor's late business partner, William Piper, there's very

little Cub in a Taylorcraft BC. In fact, he did everything he

could to do it different and do it better.

The side-by-side seating was a major departure, as were the novel, for the time, control wheels sticking out of the panel. Boarding was via an automotive type door on the right side. Eventually, another door on the other side was offered and became standard in later postwar airplanes.

The wing's airfoil,

rather than being the flat bottom Clark "Y" or USA 35

everyone else was using, was a semi-symmetrical 23000 series known

for low drag and less gentle stall characteristics. For a wing

that long to be that fast with such a small number of ponies available,

it had to have a low-drag airfoil.

The wing's airfoil,

rather than being the flat bottom Clark "Y" or USA 35

everyone else was using, was a semi-symmetrical 23000 series known

for low drag and less gentle stall characteristics. For a wing

that long to be that fast with such a small number of ponies available,

it had to have a low-drag airfoil.

The pre-war airplanes used 1025 steel tube or a combination of 1025 and 4130. Postwar airplanes are all 4130. All of them have to be inspected carefully for rust, if nothing else because they are so old and most sat out for so long.

The wings use pressed-aluminum ribs over wooden spars which also need careful inspecting. Besides age, a surprising number of the aircraft have been ground looped at least once and the incident may or may not be in their log books. The wings have a lot of overhang past the strut attach points and they could easily have spar cracks which don't show except under careful inspection.

Most Taylorcrafts use Shinn brakes which are mechanical shoe types with the lining on the drums, not the shoes. Considering that the airplane really doesn't need brakes most of the time, the brakes work just fine. Their cams can wear, but the units are easier to repair than most of the period.

The A-65 Continental engine is the standard by which all small reciprocating engines are measured. It's reliable, user friendly and easy to maintain. Parts are still available and overhauls still relatively inexpensive, when measured against more modern engines. If the mag coils are good and the timing is remotely right, the engines will catch on the first or second blade every time.

GO TO PAGE TWO FOR FLIGHT CHARACTERISTICS

For lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT REPORTS