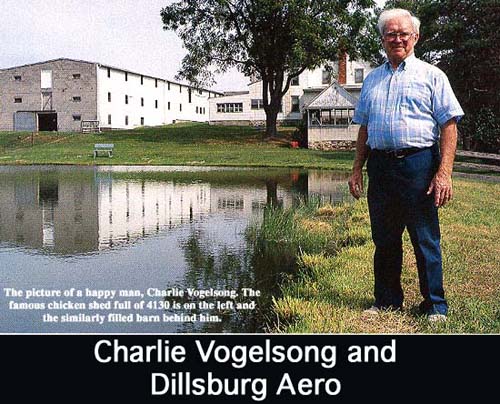

It would be really easy to get tired of guys like Charlie Vogelsong. Or may be the correct adjective should be "jealous." There he is in this incredibly pastoral setting, a stream running through the bottom of his valley and his runway working its way through the freshly cut tall grass next to the hill. All you can see from the open door of his successful business is trees and hills with no hint of civilization to spoil the view. He is surrounded by things he loves, doing something he loves and the only visible ripple in his busy, but tranquil life is the irritation caused by the mess the geese make in the pond behind his house.

Yep, it would be real easy to get jealous.

There are two different ways folks should be introduced to Charlie Vogelsong and his raw materials supply business, Dillsburg Aero. The most fun way would be to wait until after closing time and then drive on to their property and park right in the middle of the farm complex that is Dillsburg Aero. Then challenge the newcomer to find the business.

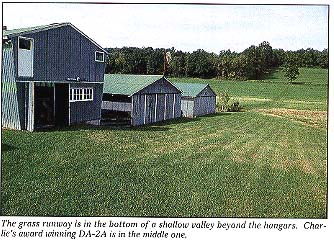

He or she would get out of the car, Ben the labrador sniffing at their feet, and initially stare around at the huge 200 foot long, two and three story chicken shed. Then they would scrutinize the nicely restored old ramp sided, over-hung typical Pennsylvania barn. Since the immaculate old structures were obviously still farm buildings and weren't part of an aircraft supply business, the curious newcomer would wander down the hill towards the runway. He'd peek in each of the metal hangars as he passed, finding a Stits Flutter bug and a Kolb in one, a pristine Davis DA-2A in another. The third was more of a workshop than a hangar but was filled with huge mailing tubes.

Still no business in sight.

Then Charlie would

come out and answer the question about where his steel and raw

materials business was located by opening one of the three big

doors that made up the entire side of the barn. In so doing he

would strip away part of the camouflage that makes his business

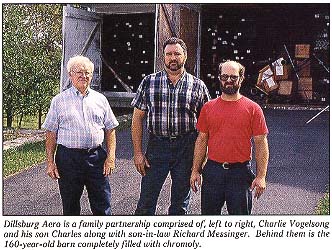

so unique. The 160 old barn is 100 % filled with steel tubing.

Every millimeter of space is neatly occupied like a giant filing

cabinet. A rectangular framework of heavy steel members goes from

under the barn clear up to the rafters, forming a dense filing

system that presents the eye with nothing but the freshly cut

ends of 4130 steel tubing.

Then Charlie would

come out and answer the question about where his steel and raw

materials business was located by opening one of the three big

doors that made up the entire side of the barn. In so doing he

would strip away part of the camouflage that makes his business

so unique. The 160 old barn is 100 % filled with steel tubing.

Every millimeter of space is neatly occupied like a giant filing

cabinet. A rectangular framework of heavy steel members goes from

under the barn clear up to the rafters, forming a dense filing

system that presents the eye with nothing but the freshly cut

ends of 4130 steel tubing.

Vogelsong enjoys the impact this has on people and can't hide a twinkle in his eye when he says, "This is, as far as we know, the largest single inventory of 4130 steel in the world."

Then he walks to the end of the chicken shed and opens another big door leading into an open bay that is his "shipping department." We put that in quotes because, as with every thing Charlie Vogelsong and Dillsburg Aero does, the emphasis is put solidly on function. On getting the job done with no frills. And, above everything else, giving the customer quality in both product and service.

"We pride ourselves on keeping the customer happy, that way they keep coming back. Our advertising budget is exactly $15 a month for a listing in the classifieds of Sport Aviation, but, right now, we have 10,000 active accounts we are serving listed in the computer. They are all over the world and all came in via word of mouth." Charlie speaks in a quiet, quick tone that picks up speed as his enthusiasm catches up with him. And no where is he more enthusiastic than when explaining Dillsburg's business.

Giving a tour of the huge chicken shed that constitutes the rest of his storage and shipping, Charlie is constantly interrupting himself to point out something that either makes up part of the Dillsburg business philosophy or that he thinks we might find interesting.

Considering that Dillsburg Aero is the largest supplier of 4130 in the world, what most people would find interesting is the complete lack of frills usually associated with a business this size. That goes back to their functionalist approach to making things happen.

The inside

of the chicken shed is, well..., the inside of a chicken shed.

There are no fancy offices. No legions of people in white shirts

scurrying back and forth. The only change since Charlie used the

building as one of the largest egg suppliers in that part of the

country is that the chickens are gone. In their place is an endless

forest of carefully constructed racks. Racks everywhere. And where

there aren't racks, there are stacks of aluminum or steel sheet.

Even the spaces between the rafters overhead hold sheared flat

stock or special sized tubing.

The inside

of the chicken shed is, well..., the inside of a chicken shed.

There are no fancy offices. No legions of people in white shirts

scurrying back and forth. The only change since Charlie used the

building as one of the largest egg suppliers in that part of the

country is that the chickens are gone. In their place is an endless

forest of carefully constructed racks. Racks everywhere. And where

there aren't racks, there are stacks of aluminum or steel sheet.

Even the spaces between the rafters overhead hold sheared flat

stock or special sized tubing.

"Notice how the racks are arranged so a man can squeeze between them," he points out. "That way, we can pick the tube up by the middle without having to drag it out. That's one of the ways we keep from scratching tubing."

That takes Charlie off on a long dissertation about how much effort they put into making sure all of their material arrives at the customer absolutely unblemished. He is a bug about scratches and everything about the way they handle and pack the material shows that. They lift, rather than drag, every piece of tubing. The aluminum sheeting is kept flat in the original aluminum mill shipping container with pieces of tissue separating each sheet. When anything leaves Dillsburg it is the way Charlie would want it himself. And Charlie is a very picky kind of guy.

Vogelsong was born and raised not far from where his farm lays today. The son of a German finish-carpenter, who among other things did fine church interiors, he was born and raised to make things.

"Yes, that's what I do. I make things," and his voice shifts into a higher gear as he starts running off a quick inventory of past projects. "I make everything. Absolutely everything. While this was still a chicken farm, I ran a fabrication shop and people came to me to build everything from firetruck bodies to race car frames and farm equipment.

"I

do it all myself. The chicken shed is one of those projects. I

built it single handed in sections right after I came back from

the service in 1945. I didn't have any money, but my uncle had

some trees on his farm and I had a one-man, six foot crosscut

saw. I felled all the trees myself and cut them into 12 foot sections

then wrestled them onto a truck to go to a saw mill. I brought

the lumber back and started building. Even the red sand for the

concrete came from my uncle's stream."

"I

do it all myself. The chicken shed is one of those projects. I

built it single handed in sections right after I came back from

the service in 1945. I didn't have any money, but my uncle had

some trees on his farm and I had a one-man, six foot crosscut

saw. I felled all the trees myself and cut them into 12 foot sections

then wrestled them onto a truck to go to a saw mill. I brought

the lumber back and started building. Even the red sand for the

concrete came from my uncle's stream."

Like most returning servicemen, Charlie had learned a lot, but few servicemen had such a broad based education as his. He says, he saw the war coming which is why he enlisted in early 1940. He was shipped down to Langly Field, Virginia where the Air Corps was just beginning to officially become a separate entity rather than a part of the cavalry. His high school training in typing and shorthand got him immediately attached to the headquarters staff. He was one of the first men put into the new organization and had a grandstand seat to watch the explosive growth that happened practically over night.

"We were so crazy down there, I wore my civilian clothes, the same shirt and same pants, for a full month before they had time to issue me a uniform. Everyday you could see how things were getting bigger and bigger and we were all working together. I would even run into Hap Arnold at the coffee pot."

In the early days of the build-up, Charlie could see where opportunities existed right and left and took advantage of as many as possible. He was accepted to flight training but after going through primary and basic hit a bureaucratic snafu that was going to put him and his entire group back one class to finish up. At that point he already had 100 hours and had learned to fly but wasn't certain he wanted to go ahead into combat training. So he quit and, by his own admission, signed up for bombardier/navigator training just so he would get shipped to the wet coast.

A quick study because of his background in building, he succeeded in training but later decided that wasn't for him either, so he was put into a replacement pool of pilots slated to fly "L" birds for the artillery. That program, however, was dropped by the government and he wound up in radio operator/mechanics school.

By this time, Charlie had already been trained to do just about everything the Air Force knew how to do. However, he had somehow gotten through all this training without firing the ubiquitous M-1 Carbine. So, in typical government fashion, he was sent to a camp in the mountains north of Salt Lake City, where he froze while learning a skill he would never need in the Air Force. However, the stay wasn't without its good points because yet another opportunity presented itself. While there he ran into an old friend, an officer, who was in charge of putting together personnel for new bomb groups. One of those was to be the 493rd in Tucson and Charlie jumped at the chance to be part of an operational bomb group. Besides, it was warm down there.

He was one of the first ten people assigned to the 493rd bomb group, Eight Air Force, and became instrumental in helping form the operational staff. He was in on the ground floor of everything having to do with making the group operational and getting it to Debach, England where they eventually flew 180 missions in B-24s and B-17s. Incidentally, it is his base and the 493rd that is shown in an aerial photo in the EAA museum as a representative WWII military base.

As a sergeant major, Charlie was one of the ranking NCOs on the base, which is another way of saying he had his fingers in everything and came out knowing how to do just about everything. He put that to use immediately upon his return.

"I left the service with $4,500 in my pocket and started looking for a farm right away. My father had always said he wanted a farm in York County, so that's where I started looking, eventually settling on this piece where we've lived ever since."

His chicken business took off from the beginning but he was always building things on the side. Always. So, it was only natural he would gravitate towards building airplanes.

"I went to Rockford sometime around 1960 and fell in love with Ray Stit's Flutter Bug. He had a way of doing things simple and strong and that appealed to me, so I bought a set of plans and started building. The airplane is still flying today."

In those days, Charlie explained, most of the steel tubing available was part of the immense amount of surplus that came out of the war. Eventually, however, that began to dry up so the steel mills began to make it again. By that time, Vogelsong's fabrication efforts were becoming more and more aviation oriented. The founder of Chapter 122 and president for nearly 30 years, the meetings were usually held in a club room he had built on top one of his hangars. Since he was so good at building things, other builders began begging him to build parts for them. He even welded up complete fuselages and tails.

"While I was building people would come in and ask if I could order them this part or that. Pretty soon I started inventorying tubing and parts and it just took off until I had to move the chickens out.

Charlie has several

very distinct guidelines around which he has built his business

and which he refuses to violate. One is that there will be no

such thing as a backorder. Never! The only way to prevent back

orders is to make certain the part is always in inventory. Not

usually in inventory, but always. That one guideline is what has

made the barn and chicken shed the repository for what is probably

the largest combined inventory of raw materials of various kinds

in the world.

Charlie has several

very distinct guidelines around which he has built his business

and which he refuses to violate. One is that there will be no

such thing as a backorder. Never! The only way to prevent back

orders is to make certain the part is always in inventory. Not

usually in inventory, but always. That one guideline is what has

made the barn and chicken shed the repository for what is probably

the largest combined inventory of raw materials of various kinds

in the world.

"We supply all the raw materials and parts you need to get a steel tube or aluminum airplane to the point you can sit in it and play with the stick. The tubing, aluminum, control cables, etc. are all in inventory. But we don't go past that point. If we can't carry every single type of a given material, we just don't go into that area."

His inventory includes steel and aluminum tubing and sheet, AN bolts and pulleys all plumbing fittings and tubing and a few other items. This may not sound like a wide spread of material until it's considered in each of those areas, such as bolts, his inventory includes a sizable number of every single AN bolt made. Not most of them, but ALL of them.

He sums it up by saying, "If we don't have it, it isn't made."

Browsing through the racks of 4130 is eye opening to anyone who considers themselves versed in the subject. He has items most don't even know exist. For instance, when was the last time you saw a bundle of 3/16" diameter, .028 wall 4130? Or how about something four inches in diameter with only a one inch hole in the middle? He has it all and everything in between.

Because his inventory is so deep, Vogelsong has a lot of buying clout with manufacturers. For instance, he says the pulley people will manufacture items they ceased making years ago because he is willing to buy so many of them.

The ability to absorb large production runs is what really put him on the steel tubing map. At first he gradually built up until he was the largest buyer of tubing from the largest distributor in the country. Then the steel mills began to wonder who this chicken farmer was who was buying so much tubing. Today, the mills come to him soliciting his business.

The size of his purchases have continued to work to his advantage until he has actually been able to reduce prices over the years. He buys in minimums of 10,000 pound lots and usually buys twice that at a time. An order that big goes in three or four times a month. This means each truck going his direction is carrying so much of his product he isn't hit with less-than-load prices. In most cases his transportation charges are a fifth or a sixth of what anyone else would pay for the same product but in lower volumes. Combine his low overhead with his lower transportation and it is easy to see why he has been able to reduce prices consistently.

Further bringing the prices down is the steel mills' willingness to work with Dillsburg for entire mill runs. Because Vogelsong's orders are so large, the mills can schedule sizable blocks of production time that are sold entirely to him. This lets them run their plant more efficiently and he realizes part of the savings.

Until recently his primary market has been homebuilders, race car builders and aerospace companies, with the racing guys being the biggest market. Lately, however, he has begun wholesaling to other sport aviation supply companies. All, or most, of the top one-stop supply companies buy their tubing from Dillsburg. He can offer them such good prices they can still mark it up and make a profit.

But pricing isn't all there is to Vogelson's near fanatical following within the hardcore homebuilding community. Most of it is built on honesty and service.

We said earlier there were two ways we'd like to introduce someone to Dillsburg. Exposing them to the camouflage of the farm buildings is the fun way. Another would be to have them get on the phone during their lunch break, call Dillsburg and order something. Depending on how many UPS zones they live away, they will get their materials as quickly as a truck can deliver them, since the order leaves the barn the same day.

Folks building airplanes in the east have become spoiled because they know they can call Dillsburg by four in the afternoon and be assured they'll have their product the next day. Most of us can tell stories of calling Charlie and asking for anything from a six inch piece of plate stock to the entire material kit for a Skybolt and have it show up 24 hours later.

"It only takes us 10 or 15 minutes to ship an order, so why not do it right then? Why wait? Every order that gets to us before three or three thirty will absolutely go out that day. If it comes in after four o'clock we'll miss a few. But not many!"

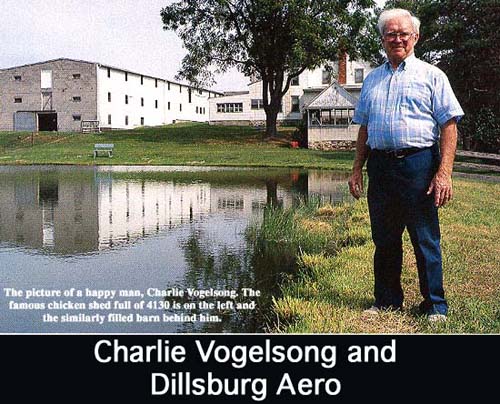

Dillsburg Aero is actually only seven people, including Charlie. His youngest son, Charles A., his son in law Richard Messinger are both partner with him in the business.Shannon Kefauver has been running the computer for the six years since she was out of high school, Bad McGaughey has been pulling material for orders for nearly twice that long and Joe Pechard does the packing. Who'd we miss? The real brains of the outfit, Charlie's wive Lucille who spends her evenings entering that days invoices in the computer. That's all there is to Dillsburg Aero and they never stop moving.

Oh yeah, if you're driving an eighteen wheeler to Dillsburg, don't forget to bring Ben a glove. He's known far and wide for the way he joyfully leaps at drivers looking for a glove to play with.

Charlie's job? He answers the phone.

"I always answer the phone because there are often technical questions along with the order and I want to make sure they get the right information. I'm a serious builder and have been for fifty years, so I can answer any question they'll have."

And he is still building. The low ceilinged room (all the ceilings are low, Pennsylvania chickens must be short!) next to the shipping area is Charlie's playroom. That's where he builds little airplanes. The current project, which has gathered a layer of dust in recent months, is a 1924 Dormoy Bathtub, an ultralight lookalike from the pioneer days of aviating that won its class in the Dayton Air Races. The engine is an original Heath converted Henderson and the entire airplane is faithful to the original drawings. It is so faithful, in fact, the Smithsonian is bugging him to finish it.

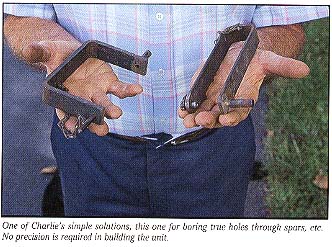

Charlie is the master tinkerer and builder, always coming up a better way to do something. He designed and sells plans for an eight foot bending brake that any homebuilder can fabricate. This trip he had some interesting looking drill jigs laying on the bench that are the soul of simplicity to make. Though requiring absolutely no accuracy while fabricating the jigs themselves, when finished they let a builder drill holes through a wood spar in a single pass and be guaranteed of the bit coming out exactly in the middle of the matching fitting hole on the other side. In one simple little piece of metal, Vogelsong took all the fear out of one of the scariest operations in homebuilding.

Charlie is a walking encyclopedia when it comes to anything having to do with practically anything, but especially steel and aluminum production and fabrication. As he explained to us, all chrome-moly tubing actually originates overseas in the form of "mother tubes." These are fat, round blivets of steel a little over a foot long, with a small hole pierced through end to end. These then form the master blanks that are shipped to the American mills to be drawn into seamless chrome-moly.

The reason the mother tubes all come from either Germany or Japan is because they have a modern steel industry that can produce tubes of that quality. The U.S. doesn't. Something about the advantages of losing a war to the U.S. fits here.

Normally Charlie is a little quiet, but once started is eager, almost driven, to share his knowledge about subjects in which he is intensely interested. During one of his compulsive explanations about steel tubing we learned why the concentricity and therefore the wall-thickness on seamless tubing varies: It is rotated once every thirty inches as it is drawn through the die so the hole in the middle drifts slightly. Another of his popular products, DOM (drawn over mandrel) tubing is perfectly concentric because it begins life as a flat sheet, is rolled and electronically butt welded and then drawn over a mandrel. Charlie says he is seeing the race car boys use more and more of that because it is almost as strong, much more concentric and less expensive.

So, Charlie Vogelsong and his York County Munchkins hustle around during the day in constant contact with hyper active builders around the world. Then it comes quitting time, the doors are closed and Dillsburg Aero ceases to exist. At that point Charlie drifts off towards one of his other serious pursuits.

He has a real love affair with electronics and was one of the first post-war ham operators (W3BQA) and would consistently frustrate the big buck operators with his ability to reach so much further around the world with his little 100 watt transmitter feeding through a Vogelsong-designed antenna. Or maybe he'll write another article for the local papers concerning some aspect of York County history. He may be on the road to give a speech that evening at an EAA chapter or fly-in on welding, or fabrication or working aluminum. Or, as he is doing right now, he may be going over samples he has panned out of a local stream where he has already proven the professional geologists wrong...there IS gold in York County.

The secret to his vitality and energy at an age most begin slowing down can be found in one of his other very serious interests, bicycling. He thinks nothing of taking off on a one day, 100 mile trip and routinely engages in 500 mile tours.

"It's the science of bicycling, as much as anything else, that interest me," he says, "The human body only puts out about 1/5 to 1/4 horse power but we can go all day on that."

Naturally, he designed and built his own bike, on which he has ridden over 25,000 miles (!) and gives seminars on bike building.

Charlie had proven there was gold in the hills of York County a long time before he started panning for it. He has found his rewards not only of the financial variety but of the personal type because, as he puts it, "...what else could I ask for? I have my toys, my family and a successful business all under one roof right where I want to live." Not many can say that.

It's nice someone can and he recognizes what he has. Charlie appreciates what the world has given him and he has reciprocated by giving back in kind.