“The Pitts is a giant magnifying glass. It shows you every little pimple and every little zit on your flying skills,” he said.

I knew my first flight with Davisson would be a hoot. Wanda and Carlita had been talking about it for weeks prior. I pushed the throttle forward on the Pitts and was immediately mashed backward against the seat and off down the runway. After a snappy rotation, I set up for a 100-mph climb, then rolled the nose toward an abbreviated turn to the crosswind.

“Feel your butt!” Davisson’s voice came over the intercom. “Look at the ball!”

It was the first moment I realized my weight was on my left cheek, a sure indication that he was right about the Pitts. What would have been a mild misstep in a regular airplane would look like a shower sequence from an Alfred Hitchcock movie in the Pitts.

I nailed the first landing...well, until I nearly took out a string of runway lights. “You have to make corrections the second anything starts to go south,” Davisson advised. “Otherwise, it’s like trying to stick a fish with a fork—by the time the fork gets there, the fish is gone,” he added, a typical Davisson aphorism.

According to Davisson, the Pitts makes all your good points better and your bad ones MUCH worse.

|

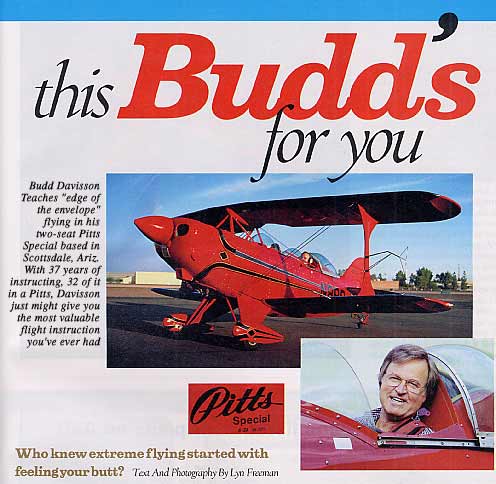

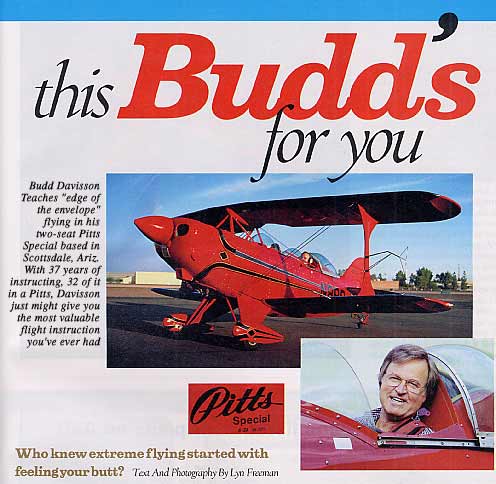

Davisson has been instructing for 37 years, 32 of them in the Pitts. His students come from all over the world with both small and large amounts of flight time. Typically, they arrive on a Sunday evening (many actually stay at his house in an extra bedroom he and his wife, Marlene, have dubbed “The B&B”). Monday morning is taken up with an extended groundschool chat in the Davisson living room, and that afternoon, students strap into the Pitts, regardless of their level of experience.

"I see absolutely no difference between a 200-hour pilot and a 20,000-hour pilot except their confidence level when they first step up to the plate. And that disappears in a day or two!” he grinned. “I can’t tell the CFIs from the rest of the pack. I had a guy recently who owned a 152 and was very proud of the 550 hours he had in it. I told him, ‘What you’ve got is the same hour 550 times,’” Davisson teased.

To most, the initial ride in the Pitts is daunting (Davisson says there’s almost always a certain “Oh, s**t!!!” factor for first-timers), and once in a while, someone tells him they’re certain they’ve bitten off more than they can chew. Davisson’s answer is always the same: “Fly with me three hours. After that, if you still feel the same way, fine. We’ll quit and I won’t charge you anything.” In more than three decades, you can count the number of takers on one hand.

Occasionally, he admits, he wakes up in the morning and his wife says, “Is your student’s name Roger? Well, you’re not flying with him anymore. You’ve been screaming about him all night!

For me, the Pitts was a heaping handful of airplane to fly. Since it’s not built to be “stable” (i.e., predisposed to return itself to straight-and-level flight), the little biplane was elated to do just about anything I asked it to do. It required constant vigilance for airspeed, pitch and rudder/aileron coordination. Get the nose slightly low and it just loves to build up airspeed—lots of it—and like a kid who’s having way too much fun, the Pitts is very reluctant to give it back. Dial in a little bank with the stick and fail to be right there with accompanying rudder, and right away there’s a “Feel your butt!” accompanying the faux pas through the headsets.

“This is all just basic flying, but people forget to fly like that because these skills just don’t matter in most airplanes. Forty percent of what I’m doing has nothing to do with the Pitts—it’s just basic flight training. I’m a holistic instructor,” Davisson grinned.

The importance of learning to coordinate all the flight controls applies to almost everyone, he suggested. “It’s very common for pilots turning final to use outside aileron and inside rudder, setting up a stall/spin accident. That’s because no one ever said, ‘Wait a minute, feel your butt!’”

After hours of chasing the Pitts all over the sky, I began to make some peace with her. I remember one approach, albeit a bit below the glideslope, in which I leveled off and squeaked it in for a great three-wheeled landing.

“That was really good,” Davisson said, “but what if you’d have lost the engine half a mile from the runway?”

“Yeah, but—” I countered.

“‘Yeah, but’ nothing,” my CFI interrupted. “I flew for 38 years without losing an engine and then had three of them pack up in 18 months, two of them in 48 hours.”

It was the last low approach I’ve shot since that moment.

Budd bases his little edge of the envelope flying school in Scottsdale, Arizona

|

If you come away with a glimpse of the goal for better airmanship, Davisson feels like he’s done his job. “I’m not the CFI to show you how to shoot a GPS approach. I haven’t owned an airplane with a navaid in it for over 30 years now. I teach the art of flying.”

And it was that “art of flying” that I began to grasp by the end of Davisson’s training course. By the end of the last flight, I had that euphoria like I had bested a mountaintop. It was almost as if I had just learned to fly not autopilots, not VOR needles, but just pure stick and rudder. During my active days as a CFI, I had gone hoarse reminding students to watch their airspeed, coordinate rudder and aileron, and on and on. I wish I could have taught them just a smidgeon of what Davisson had taught me.

I notice a lot of new skills now in my day-to-day flying, the biggest one (as you might imagine) being that I feel my butt. Of course, I’d never tell that to Davisson. It will almost certainly be left to a conversation between Wanda and Carlita. But then, how many students ever fully share with their instructors the difference that learning to fly has made in their lives?

For more information, call Budd Davisson at (602) 971-3991, or e-mail him at buddairbum@cox.net.